Today in History: October 8, 1923 – Beer Hall Putsch

Today in History: October 8, 1923 – Beer Hall Putsch The Beer Hall Putsch is mentioned time and again in the Prisoner of Night and… Read More »Today in History: October 8, 1923 – Beer Hall Putsch

Today in History: October 8, 1923 – Beer Hall Putsch The Beer Hall Putsch is mentioned time and again in the Prisoner of Night and… Read More »Today in History: October 8, 1923 – Beer Hall Putsch

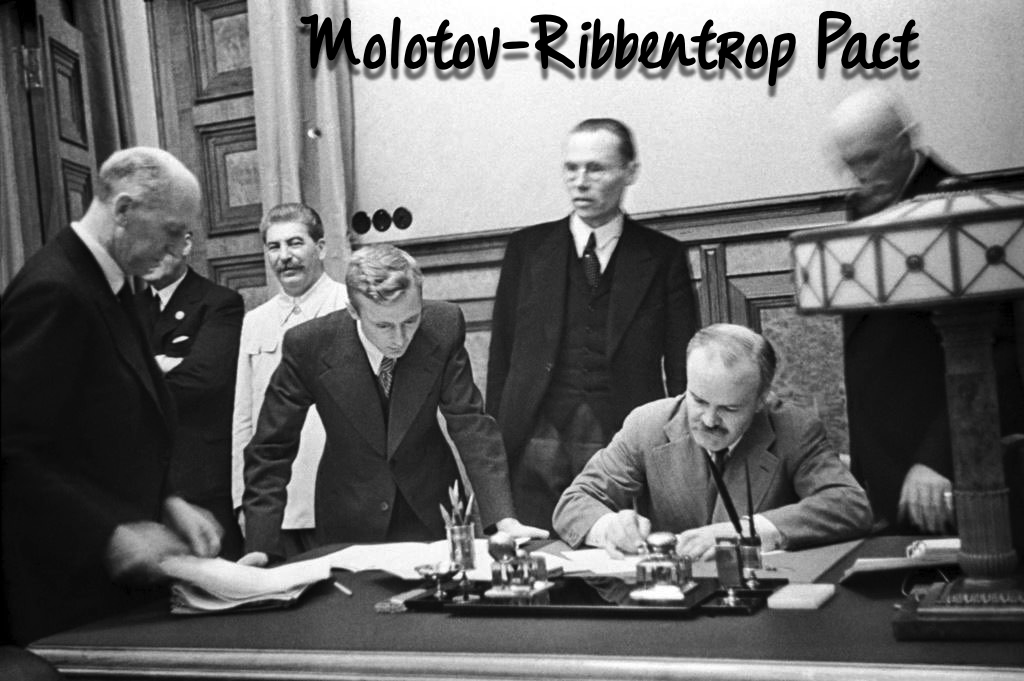

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact This topic has, admittedly, been touched on in a post about Operation Barbarossa(or will be, in this case). However, I felt a personal need… Read More »Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Three Kings: Czechoslovakian Resistance Hitler had marched into Czechoslovakia (or Slovakia) in March of 1939. In defiance of the Munich Agreement. Shortly… Read More »The Three Kings: Czechoslovakian Resistance

Czechoslovakia in WWII The long-awaited post! At least for me. I finally, finally checked out and read another WWII story, just for the sake… Read More »Czechoslovakia in WWII

Kristallnacht The Night of Broken Glass or, literally, The Night of Crystal In short: On November 9-10, 1938, Nazis “torched synagogues, vandalized Jewish homes, schools, and… Read More »Kristallnacht

Germany Occupies the Sudetenland The Sudetenland: made up of western Czechoslovakia (mostly inhabited by ethnic Germans) as well as parts of Moravia and countries… Read More »Germany Occupies the Sudetenland

Austria in WWII Admittedly, this is a repost. But, when I decided to try reading a book for each occupied country, well, I realized it… Read More »Austria in WWII

The Anschluss A little late, admittedly, but I feel like things are (at least starting to get) back on track!! On March 12, 1938,… Read More »The Anschluss

The Enemy Within: Stalin’s Purge of the Red Army It’s another short post, guys. And there is an inordinate amount of quotes this time around… Read More »The Enemy Within: Stalin’s Purge of the Red Army

The Ethiopia Campaign On October 3, 1935, “Italy attacked Ethiopia without a declaration of war” in a battle known as the De Bono Offensive (Source).… Read More »The Ethiopia Campaign