The Consequences of the Lincoln Nomination

The Kentucky-born lawyer and former Whig representative seemed like a dangerous bet to the pro-slavery Southern states. On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was the first Republican to ever win the presidency. Prior to this, though, he had won national attention in a series of debates known as the Lincoln-Douglas debates, in which Lincoln “argued against the spread of slavery, while Douglas maintained that each territory should have the right to decide whether it would become a free or slave” territory (Source).

Part of Lincoln’s success in the winning the campaign was his ability to unite the Republican party. His decision to “say nothing on points where it is probable we shall disagree” probably helpedwh (Source). Meanwhile, the Democrats were severely divided amongst three separate candidates: Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, Northern Democrat Stephen Douglas, and Constitutional Union candidate John Bell.

As soon as the announcement arrived that Lincoln had won the national election, states left and right began to threaten secession.

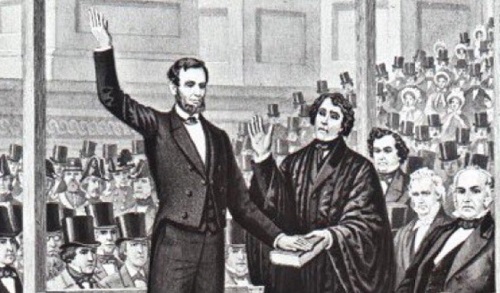

In fact, by Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1861, seven states had already seceded “and the Confederate States of America had formally been established,” with Jefferson Davis as its elected president and Alexander H. Stephens as Vice (Source). According to these Southern states, “the election of Abraham Lincoln was labeled an act of war” and they “predicted armies would come to seize slaves and force white women to marry black men” (Source). As a result, some Southern politicians began producing weaponry and even proposed kidnapping president-elect Lincoln! This all despite the fact that Lincoln never actually campaign on “taking measures against slavery in the South” (Source). Despite this, Southerners saw him as a radical abolitionist, while Northerners thought he was inexperienced and unprepared to run the country, especially at such a critical moment in history.

In his Inaugural Address, Lincoln gave the country a warning:

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. . . . You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to preserve, protect and defend it.” (Source).

[Below: Lincoln’s 1st Inauguration]

In all, eleven states left the Union. South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had all left by the time Lincoln was sworn in. Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina left after his inauguration. But more on that later.

There was more to their secession than simple slavery. It had a lot to do with states’ rights, as well. They didn’t want the Federal Government to have the authority to outlaw slavery in their territories. In the South, where agriculture was one of their main forms of bringing in revenue, slaves were in high demand. They were expected to do all the work.

On March 9, 1861, Confederate President Davis began to take action. He called up “7,700 volunteers from five states, joining volunteers in South Carolina” (Source). Then in mid-April, he had 62,000 troops stationed in former Union bases. On the 12th, Confederate forces fired the first shots of the war at Fort Sumter. It was here that the next four states seceded the Union to join the Confederacy.

But Lincoln thought secession was illegal. More than that, he was willing to use force to defend both the Union and the Federal law. Then, after the shots fired at Fort Sumter, he called for 75,000 volunteers. The Civil War had begun.

[Below: The Confederate flag]

Up Next: The Civil War Begins: The Attack on Fort Sumter