Christmas Truce

Christmas Truce A short and kinda rough post. But it’s such a sweet, hopeful story. It started on Christmas Eve. All along the… Read More »Christmas Truce

Christmas Truce A short and kinda rough post. But it’s such a sweet, hopeful story. It started on Christmas Eve. All along the… Read More »Christmas Truce

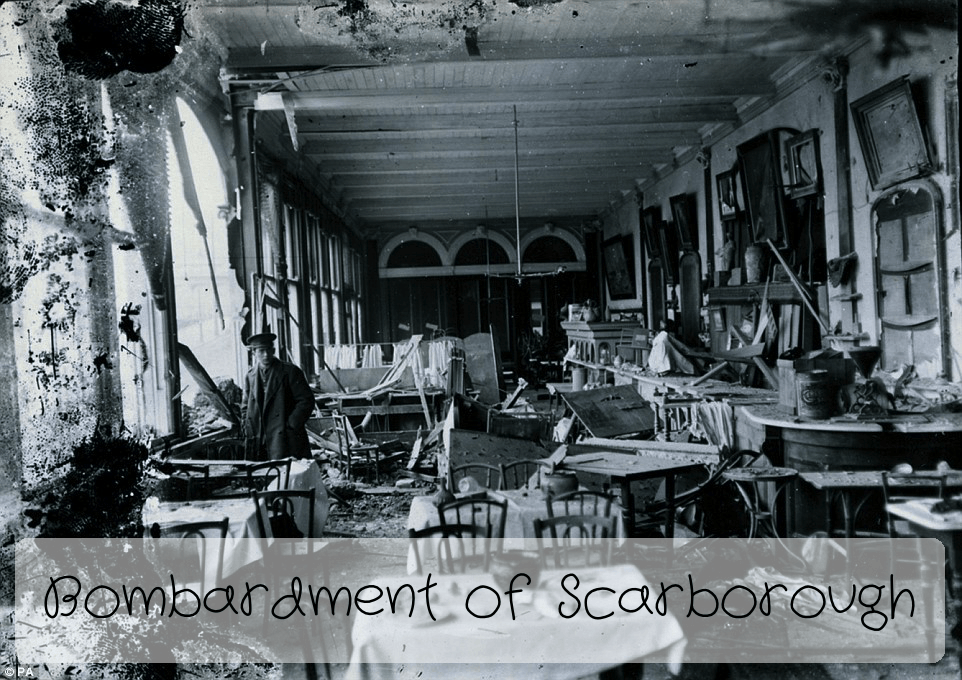

Bombardment of Scarborough At about 8 in the morning on December 16, 1914, Admiral Franz von Hipper, commander of the First High Seas Fleet Scouting… Read More »Bombardment of Scarborough

Battle of the Falkland Islands After their victory at Coronel the month prior, Admiral Graf von Spee received the news that the Glasgow was… Read More »Battle of the Falkland Islands

Battle of Coronel Since the outbreak of war, Germany’s Naval fleet had been blockaded, at least along the North Sea and the Baltic. Despite this,… Read More »Battle of Coronel

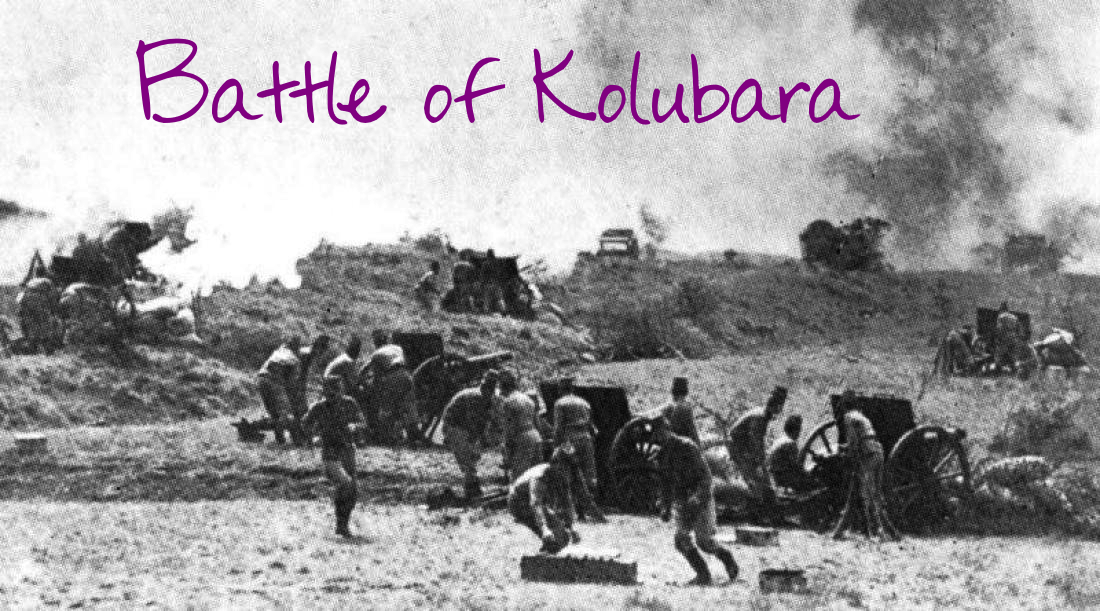

Battle of Kolubara On November 16, 1914 the Austro-Hungarian armies reached the Kolubara River, under the command of Oskar Potiorek. Thus, the Battle of Kolubara.… Read More »Battle of Kolubara

Battle of Łódź The Battle of Łódź began on November 11th, as the newly formed German 9th Army, under the command of General August von… Read More »Battle of Łódź

Armistice Day Armistice Day. Remembrance Day. Veterans Day. So many different names. So many different things to honor and remember. All the same… Read More »Armistice Day

14 Siege of Przemyśl Austria declared war on Russia on August 6, 1914. Two days later, the Russian Third Army advanced on Przemyśl.… Read More »Siege of Przemyśl (1914)

First Battle of Ypres On October 19, 1914 the Allies and Germans fought the 1st of 3 battles that took place in Ypres, Belgium. The… Read More »First Battle of Ypres

USA-eVote Wants to Help Commemorate Centennial of WWI After a lot of prayerful thought (though not many outside suggestions) USA-eVote has come to the conclusion… Read More »USA-eVote Wants to Help Commemorate Centennial of WWI