1st Battle of Lexington

1st Battle of Lexington Still wanting to secure Missouri even after their victory at Wilson’s Creek a month earlier, the Confederate General Sterling Price moved… Read More »1st Battle of Lexington

1st Battle of Lexington Still wanting to secure Missouri even after their victory at Wilson’s Creek a month earlier, the Confederate General Sterling Price moved… Read More »1st Battle of Lexington

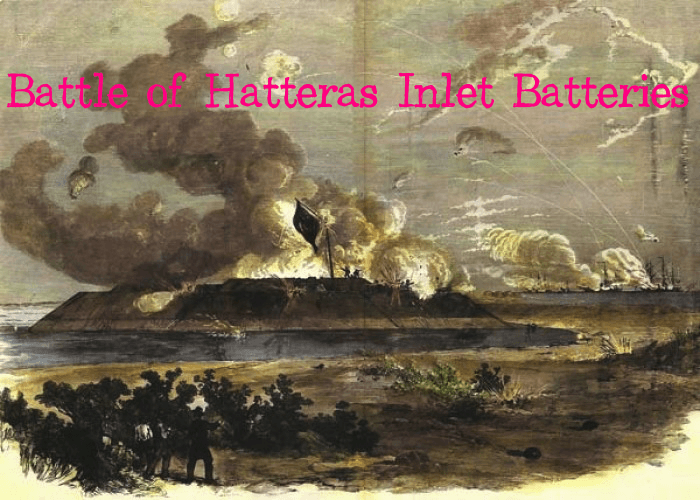

Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries As might be expected, the Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries was an amphibious offensive. Led by Major General Benjamin Butler… Read More »Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries

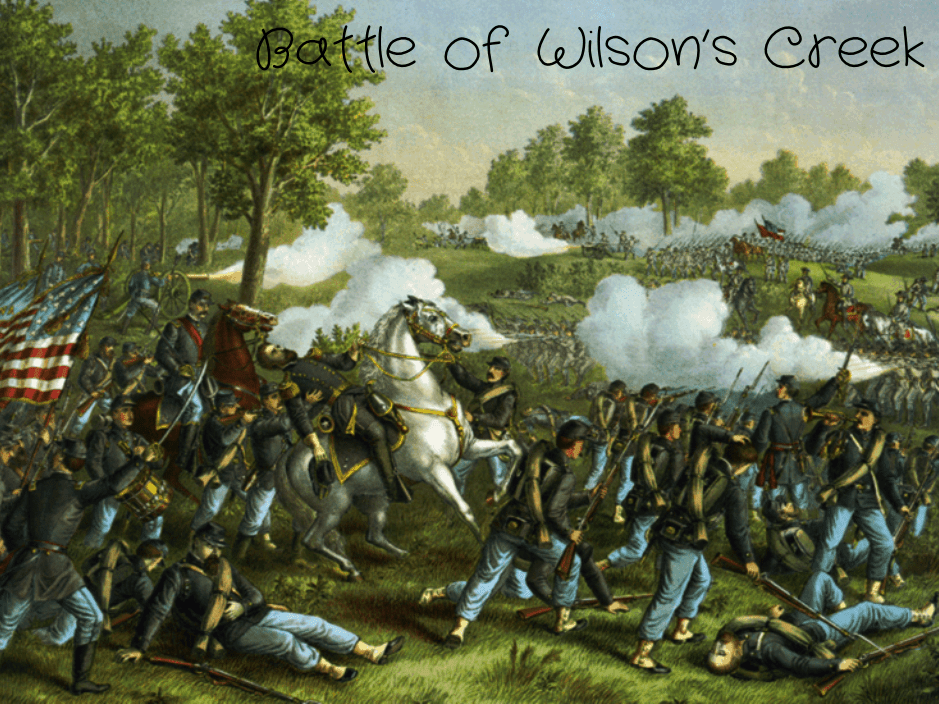

The Battle of Wilson’s Creek The first battle to take place to the west of the Mississippi was the battle at Wilson’s Creek in Missouri… Read More »The Battle of Wilson’s Creek

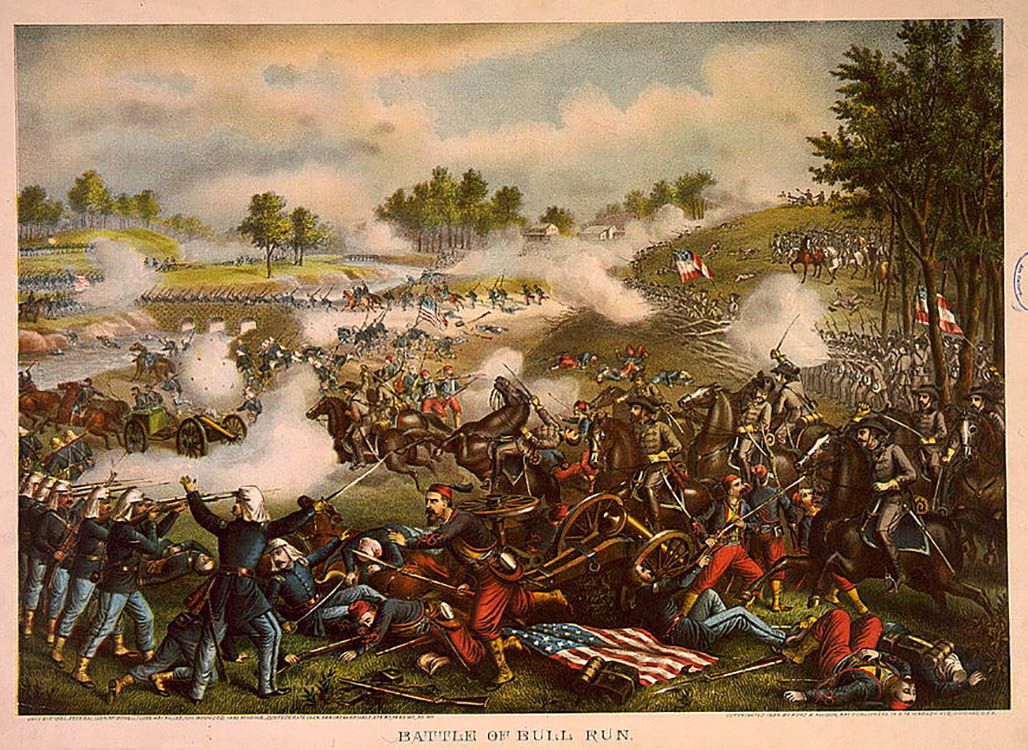

1st Battle of Bull Run On July 21, 1861 one of the biggest and best known battle of the Civil War began, the 1st Battle… Read More »1st Battle of Bull Run

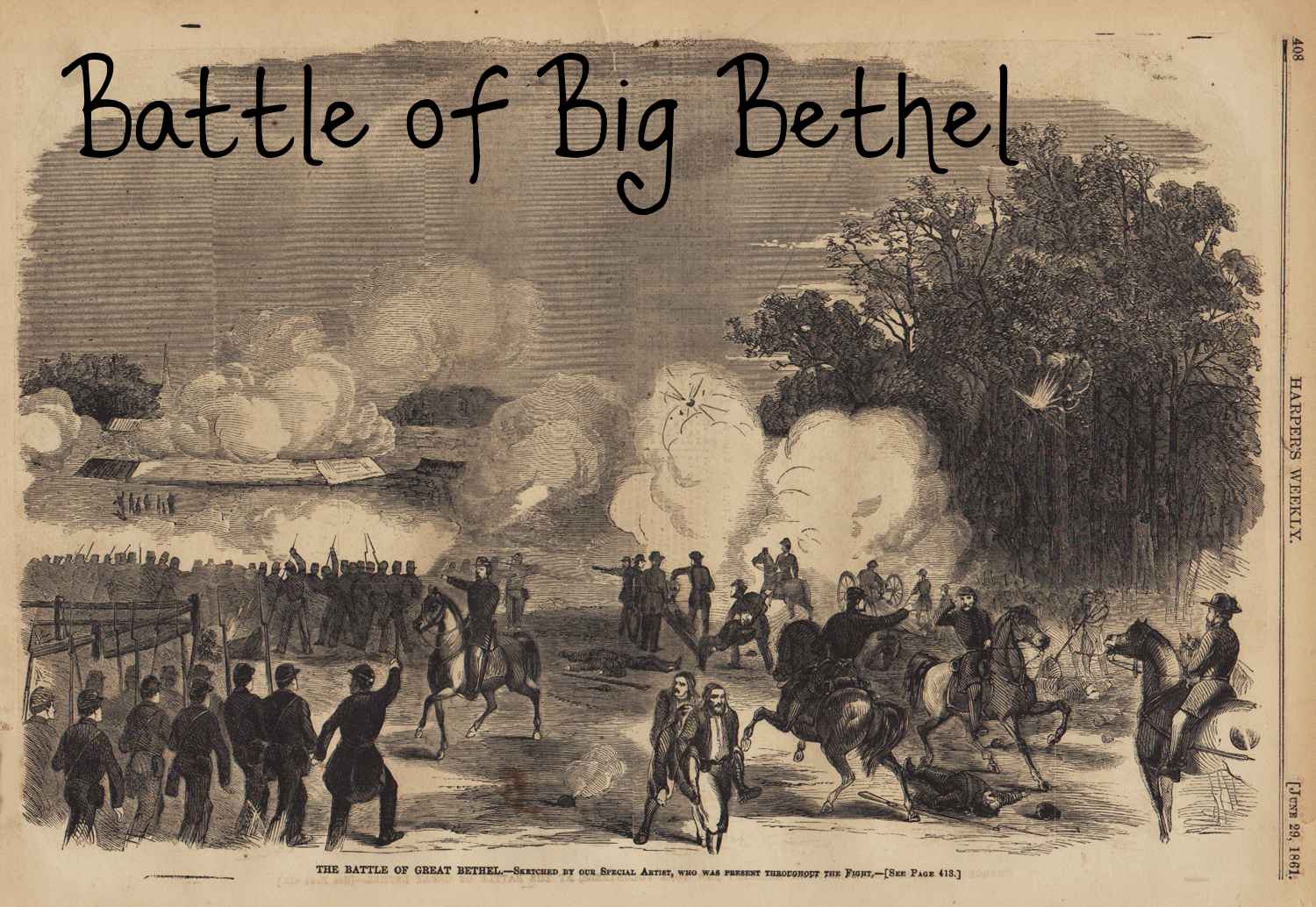

Battle of Big Bethel The Battle of Big Bethel actually took place prior to the Battle of Rich Mountain. However, it was such a minor… Read More »Battle of Big Bethel

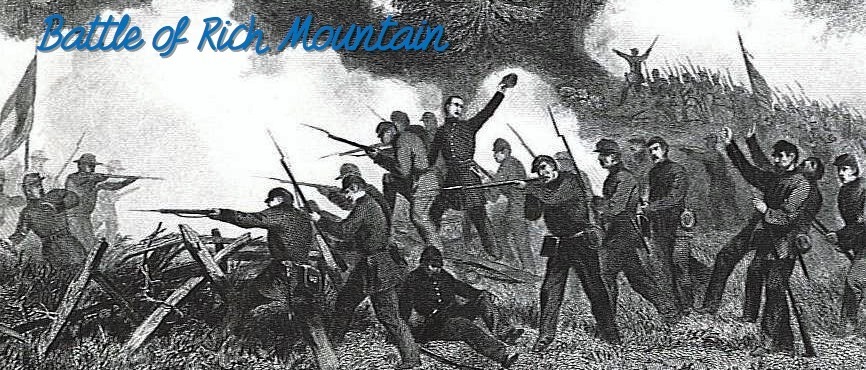

Battle of Rich Mountain In June of 1861, Major General George B. McClellan was given command of the Union forces located in western Virginia. After… Read More »Battle of Rich Mountain

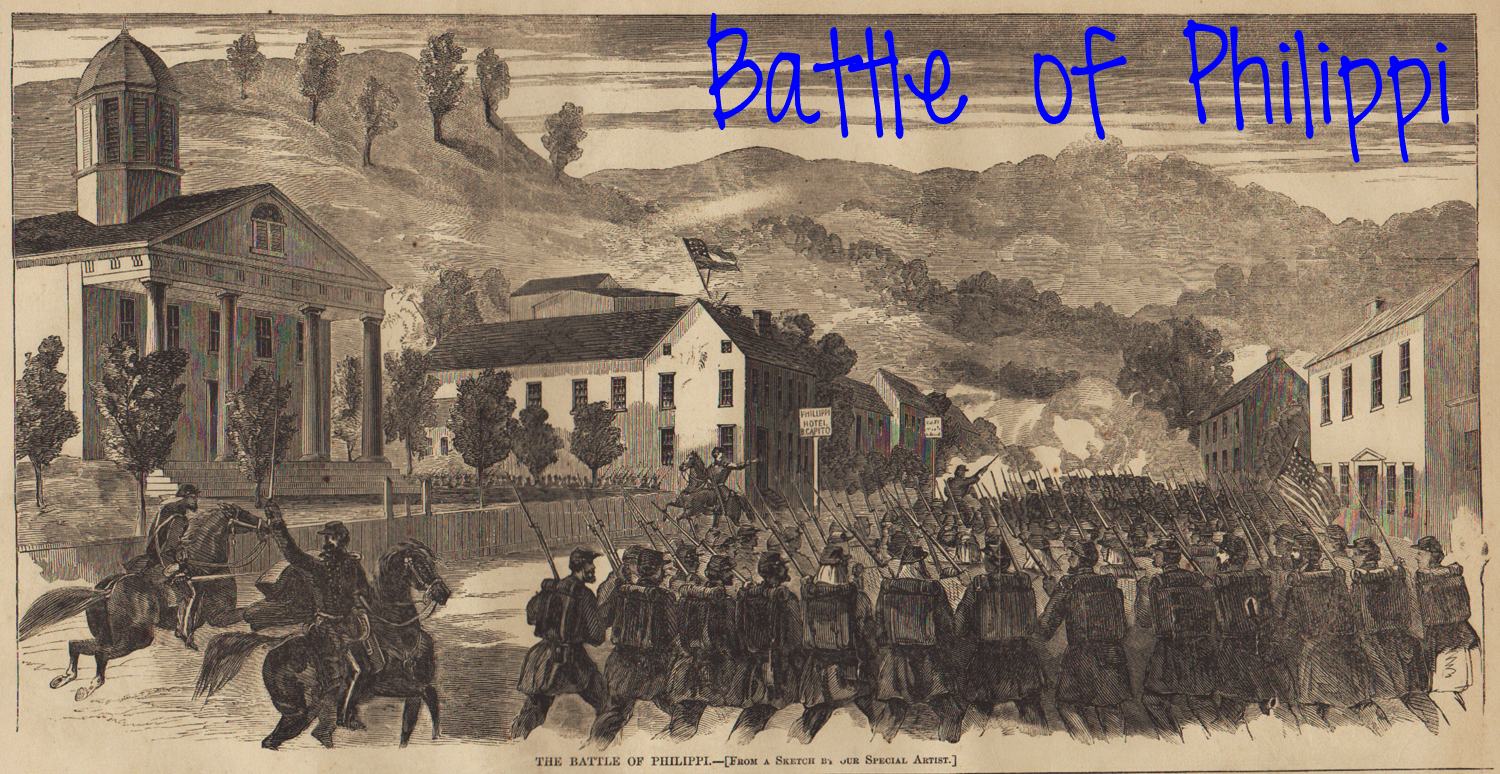

Battle of Philippi On June 3, 1961, the “first inland battle of the Civil War” began in what is today West Virginia. It was also… Read More »Battle of Philippi

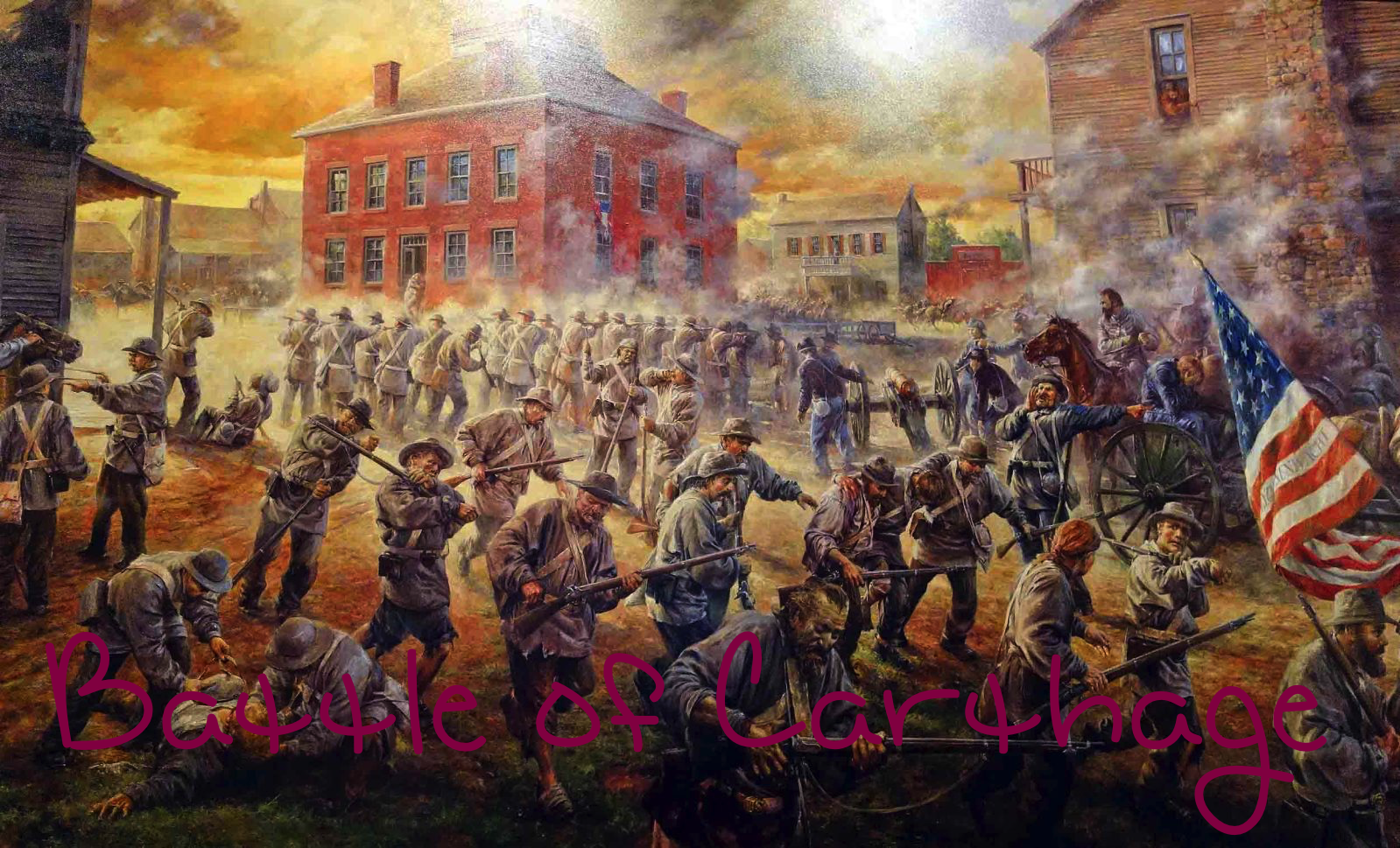

Battle of Carthage After the Battle of Fort Sumter, Missouri was deeply divided. The Missouri State Guardsmen, some 6,000 men commanded by Confederate Governor Claiborne… Read More »Battle of Carthage

The Civil War Begins: The Attack on Fort Sumter In March of 1861, President Lincoln announced his intention to resupply Fort Sumter, the lonely… Read More »The Civil War Begins: The Attack on Fort Sumter

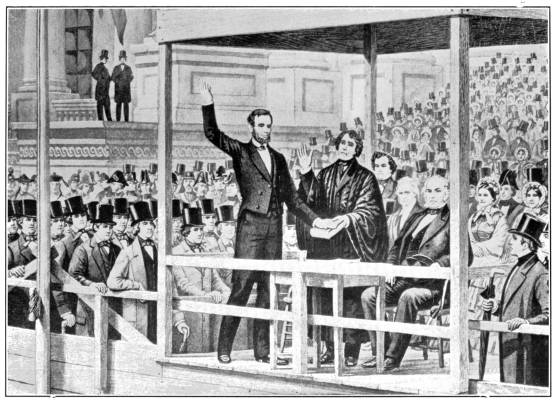

The Consequences of the Lincoln Nomination The Kentucky-born lawyer and former Whig representative seemed like a dangerous bet to the pro-slavery Southern states. On November… Read More »The Consequences of the Lincoln Nomination