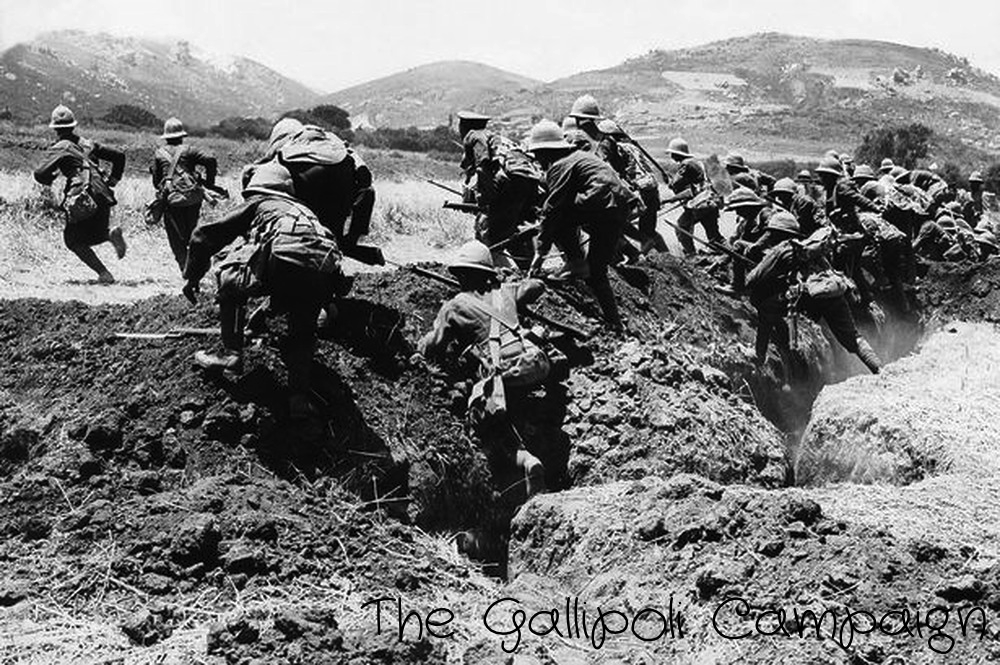

The Gallipoli Campaign

The Gallipoli Campaign started as one might expect a new campaign to start, with the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, bending over maps, searching for a new way around the impasse known as the Dardanelles Strait. This, unfortunately, resulted in utter disaster, both for the campaign and for Churchill’s career.

Well, almost – on both accounts.

Churchill, as we all know, went on to have a long and successful – if not eventful – career. And the Gallipoli Campaign would be long and eventful – if not successful.

The naval demonstrations of Churchill’s creation against the Turks turned into something of a combined naval and ground expedition. Even if the French weren’t 100% on board at the beginning. Under the command of British War Secretary Lord Kitchener’s newest protégé, Sir Ian Hamilton, a force of 75,000 British followed by 18,000 French. Men from New Zealand and Australia joined them. They Marched forward on March 25th. They were up against 84,000 Turks led by the German officer, Liman von Sanders.

Initially, von Sanders was incredibly worried about his underprepared contingent of Turks. His men were woefully underprepared and disorganized, not to mention the dreadful ammunition shortage. Little did he know, though, that Hamilton was facing a similar, if not worse, problem. In fact, Hamilton’s men were probably even more disorganized than Sander’s men. On top of this, he set sail with very little idea of how he was supposed to proceed once he arrived and a severe lack of intelligence concerning the Turkish defenses.

In other words, no one was quite prepared for the Gallipoli Campaign. Nevertheless, the Allies landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula, establishing two beachheads: Helles at the southern tip, and Gaba Tepe (later renamed Anzac Cove) on the Aegean coast. At the same time, readying for Allied invasion von Sanders began to set up defenses. Two were situated along the neck of the peninsula, by Bulair and the Gulf of Saros. Another was set along the Asian coast, at Besika Bay, and the final was set up at the southernmost tip.

The landing at Cape Helles, under the direction of Aylmer Hunter-Weston was remarkably disastrous. Despite being 35,000-stong, and the Turkish force meeting them being relatively weak, the Allies did not make much progress at Helles. First off, they were met by heavy machine gun fire. So, despite securing the Allied landing site at Helles, no progress was made at all.

[Below: Royal Irish Fusiliers]

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Soldiers_in_trench-5c05864bc9e77c000137e1ab.jpg)

On the Allied side, they found themselves not only surrounded, but also dreadfully lacking in ammunition. But the Turks were fairing no better. They could find no way to drive the Allies back. Thus, a stalemate ensued.

On August 6th, though, Hamilton decided for another try around the Turkish lines. Thus, attacks were made at both Helles and Anzac. From Helles, under Lt. General Sir Frederick Stopford, the men moved slowly forward – too slowly, it turned out, because the Turks were quickly upon them. To the south, however, the ANZACs were much luckier. Despite failure on two accounts at Chunuk Bair and Hill 971, they scored victory on Lone Pine.

But Hamilton was not to be defeated. He made yet another attempt on August 21st. They attacked Scimitar Hill and the infamous Hill 60. This particular battle lasted until the 29th, ending in yet another failure for the Allies. Hamilton, with Churchill’s permission, requested 95,000 more men, but was barely sent a quarter of that. Seeing that Gallipoli was becoming an utter failure, Hamilton called for an evacuation.

Then, because of his many failures at Gallipoli, that October, Hamilton was replaced by Lt. General Sir Charles Monro. By this point, Bulgaria had joined the Central Powers. The Turks were gaining more and more backup troops, making the Allied attacks much harder. Taking all of this into consideration, Monro recommended that the campaign be evacuated. Lord Kitchener accepted Monro’s recommendation, and by December 7th, the Allies were beginning to pull out of Gallipoli. By January 9, 1916, the last pulled out.

To have gained absolutely nothing at Gallipoli, the Allies suffered some 46,000 casualties, with another 204,000 injured. This was surprisingly smaller than what was suffered on the Turkish side, were they lost some 65,000 lives with 185,000 injuries.

Up Next:

The Garlice-Tarnów Offensive