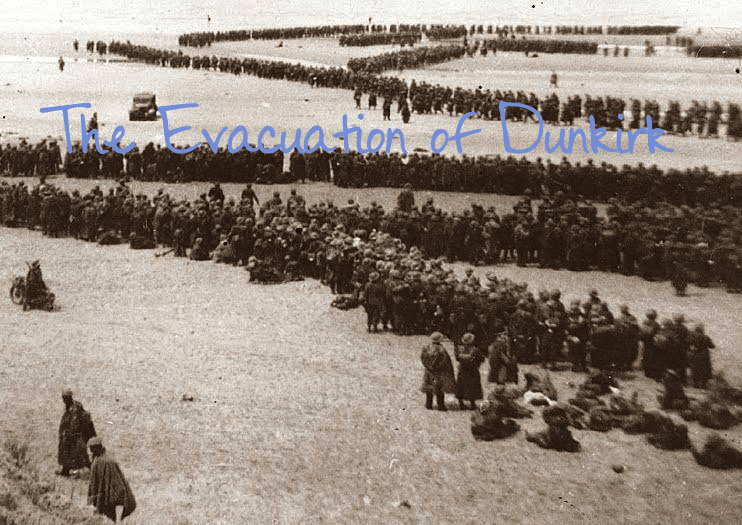

The Evacuation of Dunkirk

The Evacuation of Dunkirk “So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence. In that harbour, such a… Read More »The Evacuation of Dunkirk

The Evacuation of Dunkirk “So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence. In that harbour, such a… Read More »The Evacuation of Dunkirk

Battle of Calais The Battle of Calais started after the Germans had split the Allied armies in half at Sedan on May 14th and 15th, 1940.… Read More »Battle of Calais

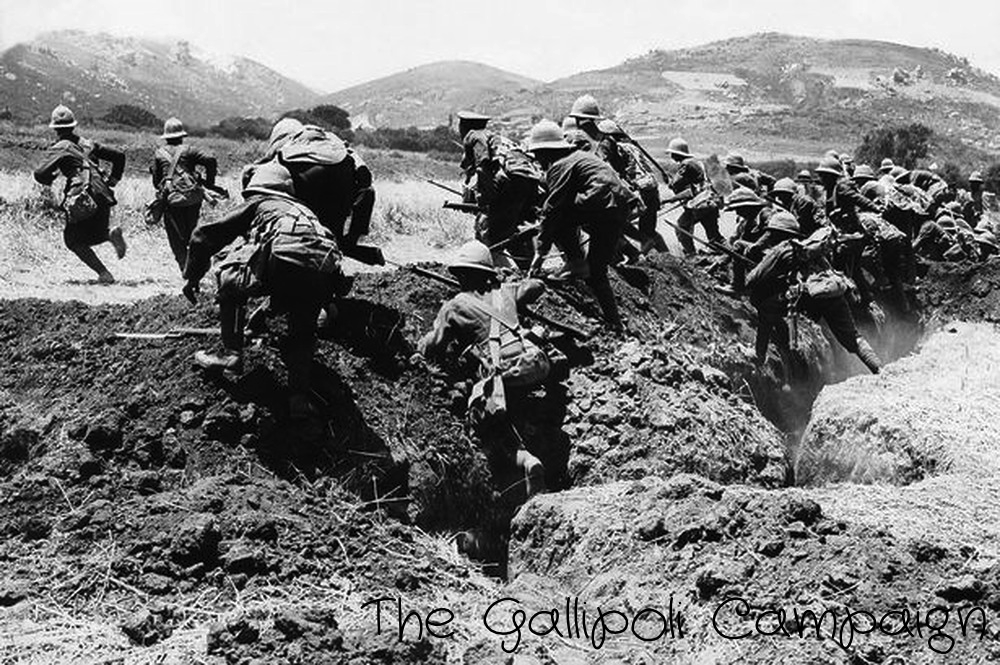

The Gallipoli Campaign The Gallipoli Campaign started as one might expect a new campaign to start, with the British First Lord of the Admiralty,… Read More »The Gallipoli Campaign

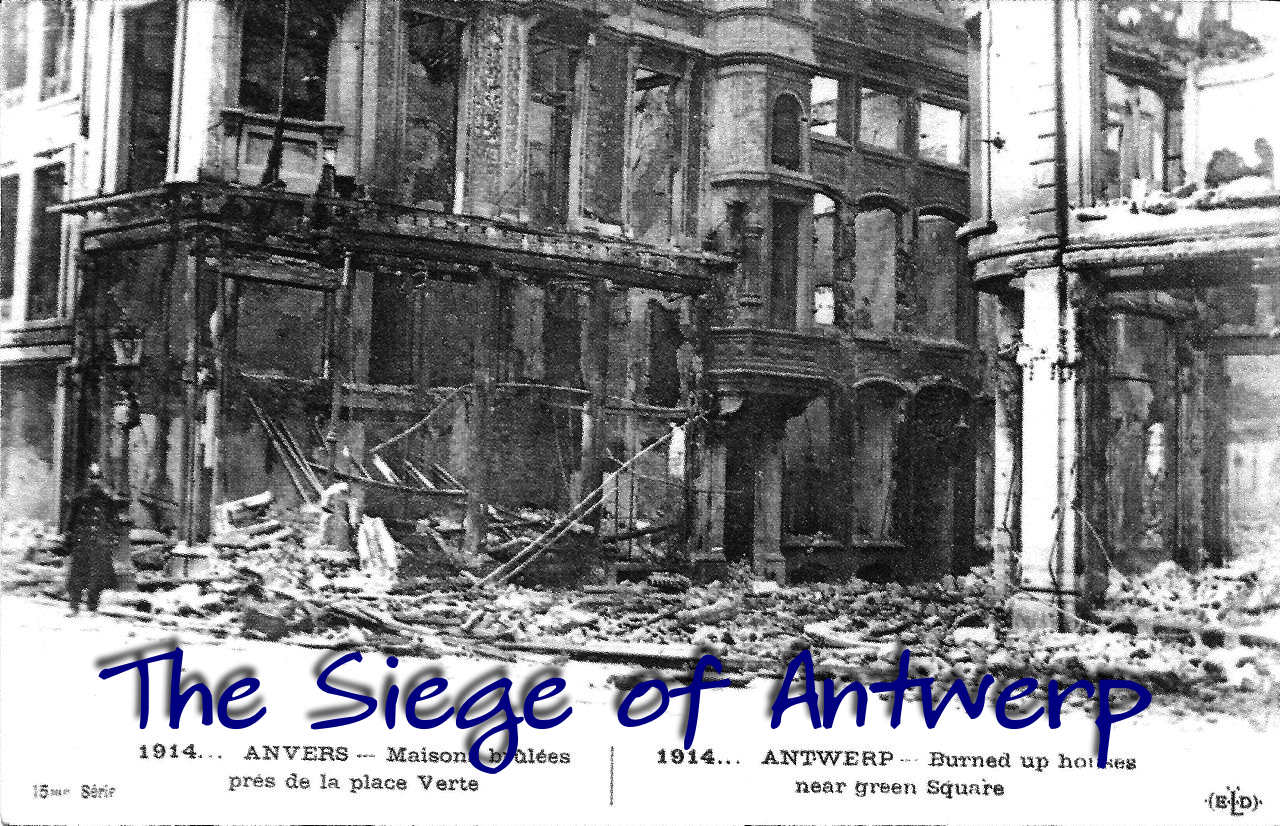

The Siege of Antwerp After the Allied victory at the Battle of the Marne, the “Race to the Sea” had begun. Both sides were racing… Read More »The Siege of Antwerp

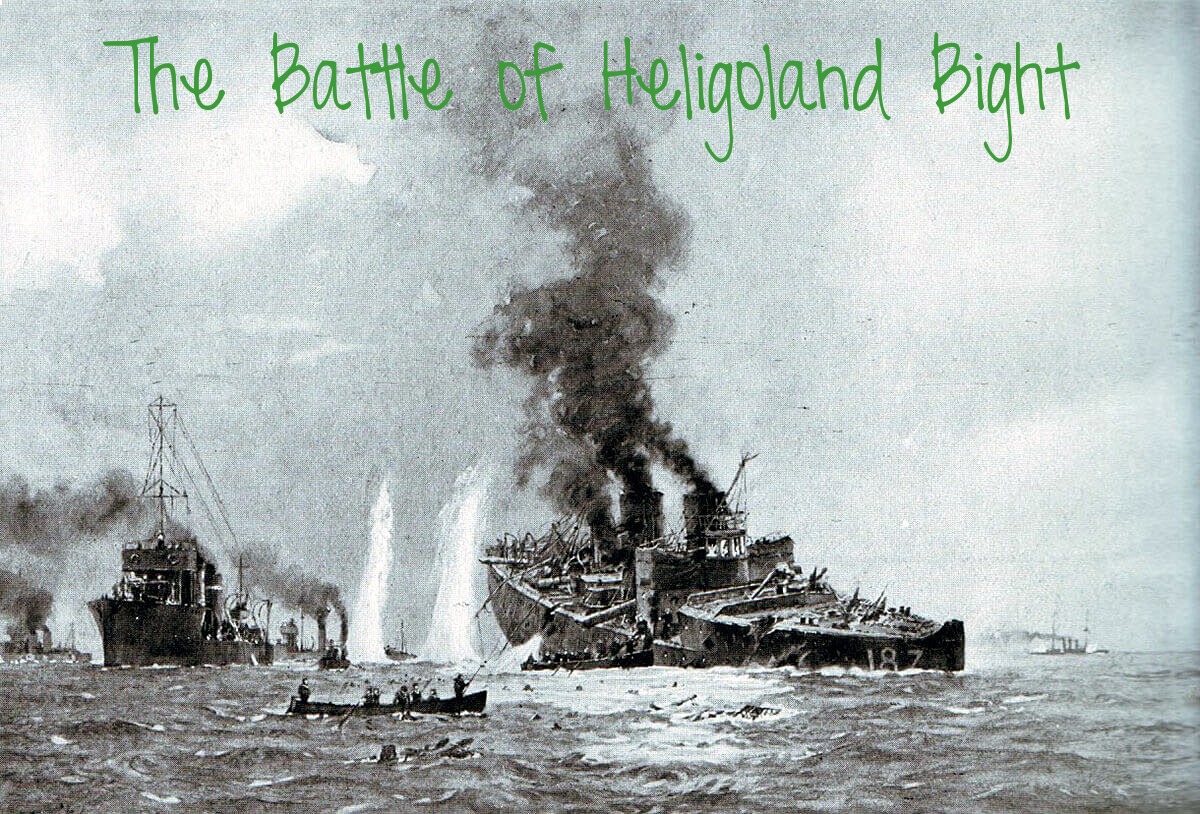

The Battle of Heligoland Bight On August 28, 1914, conflict broke out between the British and the Germany Navies in the North Sea, at the… Read More »The Battle of Heligoland Bight

A Thought Question: Expanding WWII We say that God doesn’t chose a side in war. God, however, is always on the side of freedom… Read More »A Thought Question: Expanding WWII