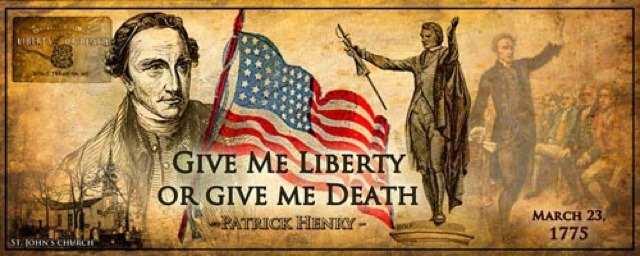

Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death

Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death On March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry gave his famous Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death Speech. In… Read More »Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death

Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death On March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry gave his famous Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death Speech. In… Read More »Give Me Liberty, Or Give Me Death

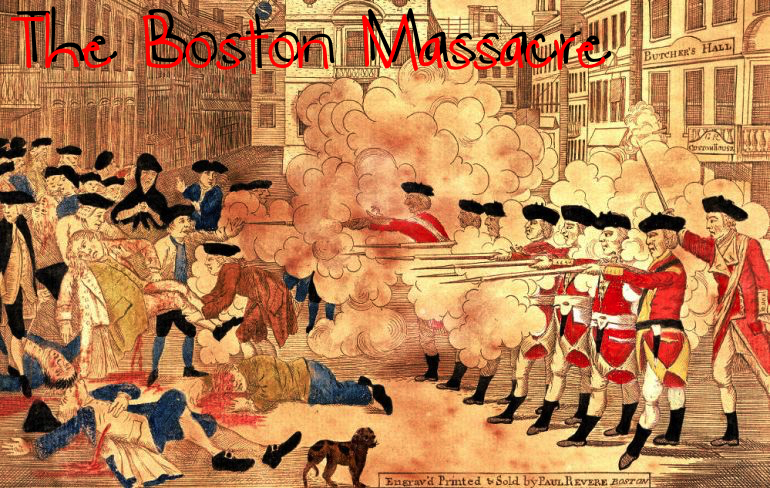

The Boston Massacre What began as a street brawl on King Street in Boston on March 5, 1770, turned into what today we know as… Read More »The Boston Massacre

“If This Be Treason, Make the Most of It!” In the midst of the uproar over the Stamp Act, Patrick Henry, newly elected to the… Read More »“If This Be Treason, Make the Most of It!”

Too Many Acts: Four Acts That Led to the American Revolution How many people want their entire paycheck to go to the government in the… Read More »Too Many Acts: Four Acts That Led to the American Revolution