The Three Kings: Czechoslovakian Resistance

Hitler had marched into Czechoslovakia (or Slovakia) in March of 1939. In defiance of the Munich Agreement. Shortly thereafter, “a Czech representative council had been established in London” (Source). In early 1940, they made contact with the Czechoslovakian resistance. At that time, all of the various resistance groups morphed into one large group: The Central Leadership of Resistance at Home (UVOD). However, Communist resistance groups refused to join forces with non-communist groups, mostly because of the Nazi-Soviet Pack (aka the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact).

See, like all European occupied countries (whether occupied by Hitler or Stalin, it didn’t matter) the Czechoslovakians were treated cruelly. Collaborators helped the Nazis keep everyone under control. Additionally, many thousands of Germans were deported to Germany to work as forced laborers (aka slaves). Back in Czechoslovakia, the people were forced to ration food and salaries, and weren’t given nearly what they needed of either.

Then, in September of 1941, Hitler sent Reinhard Heydrich to Prague. Within weeks, some 5,000 people were rounded up – all those that were thought to be involved with the Resistance. Unfortunately for Heydrich, this only seemed to spur on the Resistance. Acts of sabotage grew exponentially. These included bomb attacks, setting fires, as well as publishing and distributing pamphlets. One of their favorite acts was “reporting news to the government-in-exile” (Source).

The UVOD would receive intelligence (information) from their contact, Agent Paul Thümmeland, who cooperated with both postal workers and railway employees. Another good source of information was actually Czech policemen (unlike in France, clearly), who were always ready and willing to act as translators for the Germans! This, of course, supplied them with vital intel.

Of course, all of this resistance work drove Heydrich crazy.

[Below: Bombing of Prague]

One of the major components of the Resistance was “The Three Kings” codenamed as such by, of all people, the Nazis (the Prague Gestapo, to be exact) . . . mostly because they wanted to, well, do away with them. The Three Kings, established in 1939, was compromised of only three members. That’s right. Three. Josef Mašín, Václav Morávek, and Josef Balabán.

They were best known for setting off two different bomb assassinations in Berlin. The first was “aimed at the German Ministry of Airship and Police Headquarters,” the second aimed at Heinrich Himmler (Source). The first was successful, the second . . . not so much. See, Himmler’s train arrived . . . at the wrong station!

In the first bombing, Mašín’s brother-in-law (pretending to be a German collaborator) was the one to place a suitcase of explosives in the headquarters and then another at the Ministry of Air Travel.

They were also responsible for bomb attacks in Leipzig and Munich, though these acts weren’t nearly as well known. They also successfully bombed a transport of German soldiers “by adding an explosive to coal on the locomotive’s tender” (Private).

Then, in May of 1942, another resistance movement took place: Operation Anthropoid. Operation Anthropoid was mission to assassinate Heydrich. This time around, the British sent out two trained Czech agents. On the whole, the UVOD was not exactly supportive. Not that they didn’t want to get rid of Heydrich, I’m sure they did. But, what they feared was the consequences of taking out such a high ranking Nazi officer.

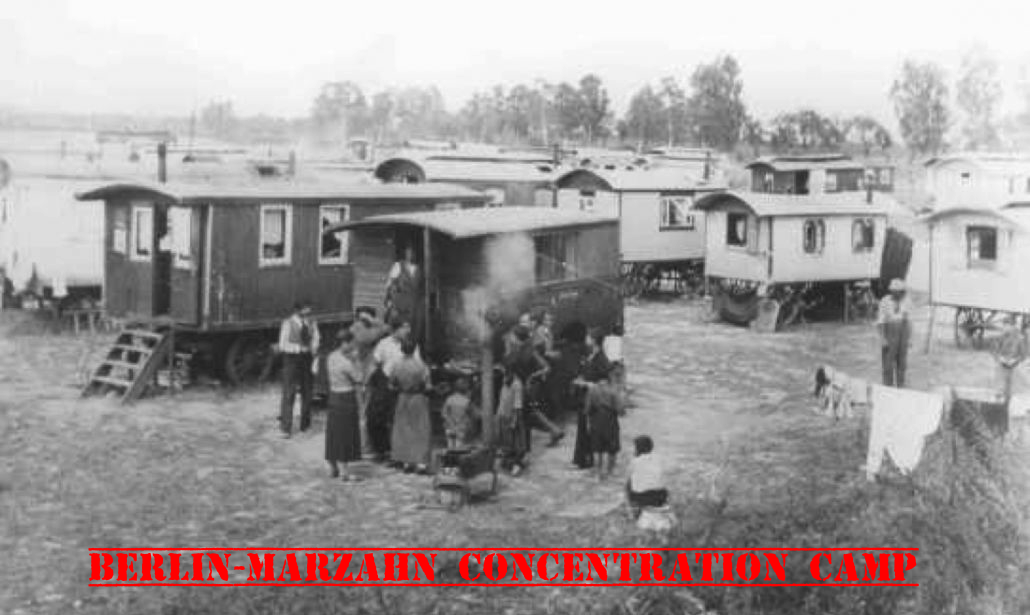

Turned out, they had every reason to be fearful of the consequences. As a result of the assassination, “as the village of Lidice and Lezaky were destroyed along with their inhabitants, thousands of hostages were shot and many more sent to concentration camps” (Source). Additionally, the UVOD suffered greatly. As a result, they were forced to operate in separate units again. Furthermore, the base in London informed them that they could only act on the “defensive.” AKA: Intelligence.

Now, the Czechs were very good at intelligence, but they wanted something more efficient, specifically those loyal to Stalin, of all people. So, they decided to join up with the Red Army or the Russian resistance fighters. Eventually, the Germans did retreat. But then, the Red Army began to assert itself in Czechoslovakia, and they dominated all of the key resistance posts. I’d be willing to bet that the Czechs regretted that collaboration.

Meanwhile, the seven Czechs were forced to hide in the nearby Parachutists Church. Actually, they hid in the crypt of the church.

In the early morning hours of July 18, 1942, 700 SS members stormed the church and began shooting. They’d been tipped off by a fellow parachutist, Karel Čurda, who collaborated with the Gestapo for one million Reichsmarks. The Seven Czechs and Slavs were able to hold out for hours. But then, the Nazis flooded the basement with fire hoses.

Instead of facing capture, the seven men took their lives. “Some shot themselves, others took cyanide” (Source).

This act is still important to Czechs today because it shows that they never gave in to Nazi occupation, they fought, and were willing to give their lives, if only to see their country free again.

[Below: Parachutist Church crypt]

Up Next:

Denmark in WWII