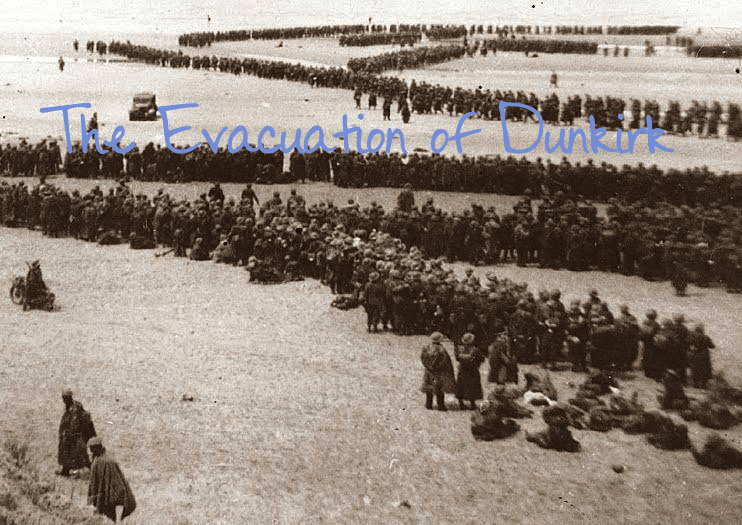

The Evacuation of Dunkirk

The Evacuation of Dunkirk “So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence. In that harbour, such a… Read More »The Evacuation of Dunkirk

The Evacuation of Dunkirk “So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence. In that harbour, such a… Read More »The Evacuation of Dunkirk

Battle of Calais The Battle of Calais started after the Germans had split the Allied armies in half at Sedan on May 14th and 15th, 1940.… Read More »Battle of Calais

The September Campaign On September 1, 1939, the Axis Powers launched the September Campaign – their invasion of Poland. Over a million and… Read More »The September Campaign

First Battle Of The Aisne Thanks to the Great War channel on youtube, I discovered that I missed a battle in my attempt to chronologically… Read More »First Battle Of The Aisne

First Battle of Ypres On October 19, 1914 the Allies and Germans fought the 1st of 3 battles that took place in Ypres, Belgium. The… Read More »First Battle of Ypres

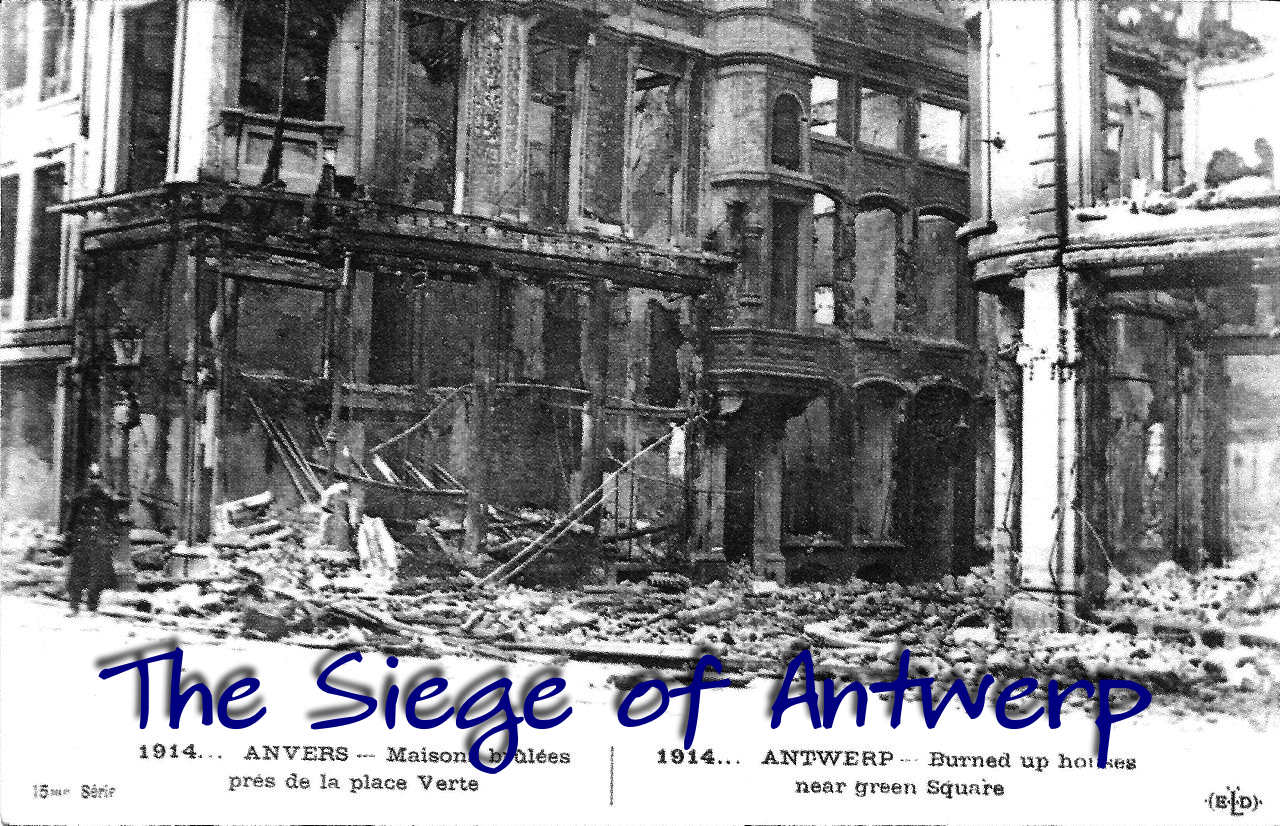

The Siege of Antwerp After the Allied victory at the Battle of the Marne, the “Race to the Sea” had begun. Both sides were racing… Read More »The Siege of Antwerp