Rally ‘Round the Flag

Rally ‘Round the Flag Yes, we’ll rally round the flag, boys, We’ll rally once again, Shouting the battle cry of Freedom, We will rally from… Read More »Rally ‘Round the Flag

Rally ‘Round the Flag Yes, we’ll rally round the flag, boys, We’ll rally once again, Shouting the battle cry of Freedom, We will rally from… Read More »Rally ‘Round the Flag

The Civil War Begins: The Attack on Fort Sumter In March of 1861, President Lincoln announced his intention to resupply Fort Sumter, the lonely… Read More »The Civil War Begins: The Attack on Fort Sumter

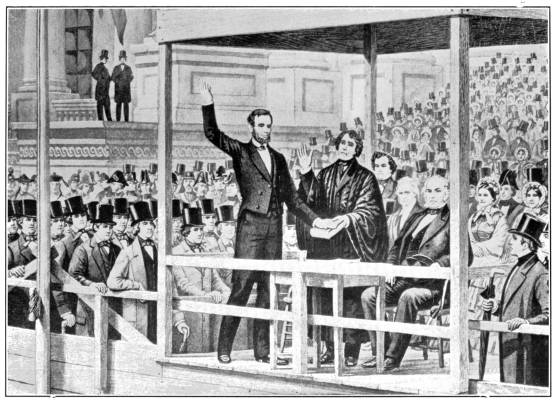

The Consequences of the Lincoln Nomination The Kentucky-born lawyer and former Whig representative seemed like a dangerous bet to the pro-slavery Southern states. On November… Read More »The Consequences of the Lincoln Nomination

Pre-Civil War Timeline (Source). The time between 1787, when the U.S. Constitution was ratified to claim that slaves counted as three-fifths of a person,… Read More »Pre-Civil War Timeline