Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp

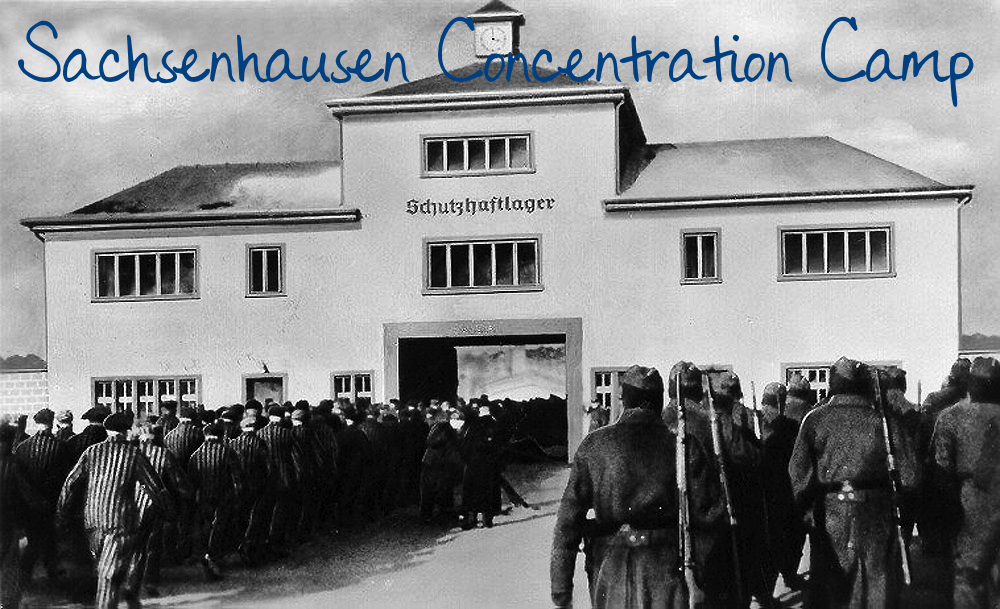

Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp was built in July 0f 1936 by prisoners from other camps in Oranienburg, Germany. Eventually, 44 other subcamps to Sachsenhausen were built. It housed its first prisoners in September 1938 under the commanding of Hermann Baranowski, Hans Loritz, Walter Eisfeld, and Anton Kaindl.

At first, the main prisoners at Sachsenhausen were German Communists, social democrats, and Jews, as well as some asocials, numbering some 5,000 in total. Later Soviet POWs were also sent to the camp. Two months after Sachsenhausen was opened, Kristallnacht shook the streets of Germany. Afterwards, some 1,800 more Jews were rounded up and sent to the camp. A mere year later, the prisoner count had climbed to 11,300. “Hundreds of prisoners died as the result of a typhus epidemic and the refusal of medical aid to the sick. The corpses were initially taken to the crematorium in Berlin; it was in April 1940 that a crematorium was set up in the camp itself. Executions were a daily occurrence. . . . In autumn 1941, the effects of the gas wagons were tested on the prisoners in Sachsenhausen ahead of it’s planned use in the east” (Source). In 1939 alone, more than 800 prisoners died due to lack of medical care. The number, however, jumped significantly in 1940, to a whopping 4,000 deaths.

Like other concentration camps across Europe during WWII, the punishments were harsh, to say the least. These included daily executions, the “Sachsenhausen Salute” – in which prisoners were forced to squat while holding their hands outstretched in front of them – as well as the unusual punishment of walking around the perimeter of the camp, essentially wearing in military footwear. Some were punished by being sent to the Punishment Company, where they were killed through torture, beatings, and starvation. Worse yet, “Some would be suspended from posts by their wrists tied behind their backs. In cases such as attempted escape, there would [be] a public hanging in front of the assembled prisoners” (Source).

While the SS guards lived and used several brick buildings, the inmates themselves, of course, lived in overcrowded wooden barracks. These were just beyond the roll call area. “The layout was intended to allow the machine gun post in the entrance gate to dominate the camp but in practice it was necessary to add additional watchtowers to the perimeter” (Source).

The standard barrack layout was two accommodation areas linked by common washing and storage areas. Heating was minimal” (Source). There was also in infirmary, a camp kitchen, as well as a kitchen laundry. Just outside the perimeter of the camp was an industrial yard containing SS workshops. Prisoners were forced to work here. In fact, the Heinkel He 177 bomber was made at Sachsenhausen. Between 6,000 and 8,000 prisoners were forced to labor on the He 177 during the workshop’s operation.

Then, on January 31, 1942, the SS demanded that prisoners would build “Station Z.” The sole purpose of “Station Z” was extermination. Following this, the SS of Sachsenhausen invited high ranking Nazi officers to watch the inauguration of their new installation. On May 29, the SS tried out “Station Z” with the execution of 96 Jews. The following March, a gas chamber was added.

As the Allied advance began in 1944 & 45, the numbers in Sachsenhausen grew exponentially. This continued until April 20th & 21st, when, as the Red Army drew in, the SS began the Death March. “They were divided in groups of 400. The SS intended to embark them on ships then sink those ships” (Source). However, so many of the prisoners were already too weak to walk. Thus, thousands were shot.

Sachsenhausen was liberated by the Red Army on April 22nd. At that time some 3,000 prisoners were still interned. Overall, it is estimated that some 200,000 prisoners passed through Sachsenhausen, some 30,000-35,000 perishing.

However, what isn’t often discussed is that the Soviets kept it as a concentration camp. Soviet Special Camp No. 7 moved into Sachsenhausen. Here, many German prisoners were kept as well as “political prisoners and inmates sentenced by the Soviet Military Tribunal” (Source). These included anti-Communists and others opposed to the Soviets. The Soviets kept the camp open for another five years, during which time some 60,000 more people were interned. Some 12,000 had died of malnutrition and disease.

In 1956, the East German government decided to make the former camp and national memorial. It was inaugurated on April 22, 1961. Then in 1990, mass graves from the Soviet camp were discovered. Today there is a museum to document the camp’s time as Sachsenhausen and a museum documenting it’s time as a Soviet camp.