Danish Resistance

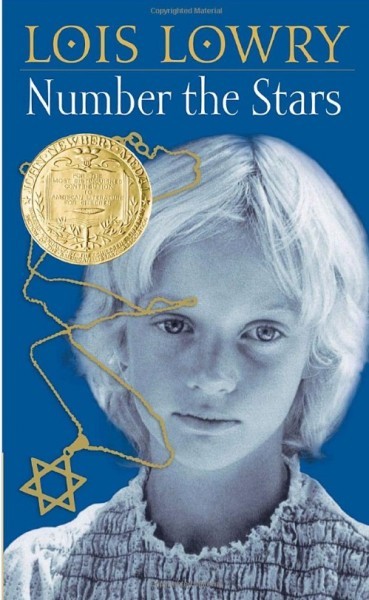

Number the Stars is likely one of the books that all 90’s kids read at some point in grade school. Maybe for class, maybe just because they saw it on the shelf at their local library of Barns ‘n Noble, or maybe their parents were trying to teach them about history. Either way, it was likely one of our first encounters with the Holocaust (though, to be fair, there were a number of amazing Holocaust stories for children, even back then). Number the Stars by Lois Lowry (yes the author of The Giver) showed us what real fear and oppression looked like.

Summary:

Ten-year-old Annemarie Johansen lives in Nazi-occupied Denmark. She knows what a world is like with soldiers on every street corner. And she knows simple things about how to avoid detection, such as not running through the street. Nazi soldiers on every street corner is scary enough … but Nazi soldiers banging on the front door is much, much worse. See, it wasn’t until her parents took in her best friend, Ellen Rosen, that Annemarie realized just how scary Nazi soldiers could really be. But one night, they did come knocking, leaving the Johansen’s to pretend that Ellen wasn’t really Jewish, but another daughter. Then, the real danger began as the family has to risk everything to get Ellen’s family out of Nazi-occupied Denmark and into the safety of neutral Sweden.

Though Denmark was invaded by the Nazis on April 9, 1940, resistance in Denmark didn’t start until the summer of 1942, thanks to other Allied nations, namely Britain.

Initially, the Danish fought back in non-violent ways. Mostly, they published newspapers (both legal and illegal) and books, broadcasted Allied radio programs, “preparing for the prospect of armed combat and engaging in weapon smuggling for the possibility of active battle, relaying information about Nazi activities and positions to Allied contact via radio and bicycle, detonating explosives at major Nazi resource sites in Denmark, and numerous other ways” (Source).

In fact, journalism gave the Danish resisters the perfect platform. Remember, despite being under Nazi oppression, the Danes were allowed to publish their own newspapers. And, despite the Nazi restrictions, the Danes grew very creative in putting out otherwise restricted information. “Danish newspapers ran suggestive headlines and stories and juxtaposed articles in a way that subtly made fun of, or criticized Germany. Layout departments manipulated the organization of newspapers in every way possible, sometimes placing stories of Nazi victories at the bottom of the page or end of a section” (Source). In addition to the official newspapers, the Danish resistance published underground newspapers. These would contain the stories of Allied victory, not allowed in the national papers. They also covered resistance acts, supported resistance groups, and printed other stories or information not allowed in the national papers.

Radio personalities also got creative. Using their voices, they could hint at their German disapproval. For example, they read the Nazi reports or war reports of Nazi victory in flat, low, unenthusiastic voices. Additionally, “an employee of Denmarks Radio was able to transmit short messages to Britain through the national broadcasting network” (Source). Presumably, this was done through coded messages, such as was seen in the French Resistance.

[Below: Resistance members burning papers from Dagmarhus – Nazi headquarters during the occupation]

Then, of course, there was the ‘V’ campaign. Or better known as ‘V’ for Victory (today the symbol is often confused for peace, but the origins go back much further and carries a much different meaning.) ‘V’ for Victory officially started in Britain, but it boosted morale all across Europe and even found root in America. To prisoners, such as the Danish, it could also be a small way of resisting. “Danes painted V’s on posters and on building walls. V’s were also prominently included in letters and cards, and Danish newspapers emphasized V-words in articles, headlines, and advertisements. Radio announcers purposefully used words beginning with V in their programs as a way to [subtly] raise the hopes and spirits of listeners” (Source).

Much of this information was gathered by military intelligence, who had contacts within the SOE. This provided resistance groups, and thus citizens, with information about German army locations, political developments, and Danish fortifications. After the Nazis removed Danish military from Jutland, these acts were carried out by plainclothes and reserves.

Around September 1943, a Danish underground government was formed, much to the relief of other Allied countries, who had been worrying that Denmark was collaborating with the Nazis. The Danish Freedom Council formed other, separate resistance groups into one large, Allied-recognized group. Under this title, they suggested to the RAF (Royal Air Force), that an important bombing location was the Gestapo headquarters at Shellhus, in the center of Copenhagen. Operation Carthage was the result. It was essentially a low-level raid. But more on that in a later post dedicated to the operation.

Also in 1943, the Resistance was able to save “all but 500 of Denmark’s Jewish population of 7,000-8,000 from being sent to the Nazi concentration camps by helping transport them to neutral Sweden, where they were offered asylum” (Source). They sought asylum from oppression, abuse, and, likely, death.

Strikes also played a huge role, though, they were mostly organized by the communists. They spread across 17 different towns, across factories, shops, and even offices. All closed down and the people rioted. In Copenhagen, no riots broke out, but they made sure that disturbances did spread across the town. The authorities, both political and union, tried their hardest to put a stop to both the strikes and the unrest in general. Hitler demanded that a state of emergency be enacted as well as the death penalty for sabotage. Of course, the Danish refused to cooperate.

As the German military continued to grow and grow in Denmark, the resistance numbers grew along with it. In fact, they numbered some 20,000 by the end of 1944 and then to an astonishing 50,000 by their liberation in ’45. The British and Swedish armed the resistance groups with handguns, and in the case of the British, with bombs. Additionally, the base of the Danish resistance moved to Stockholm because “they were far safer than in Denmark – but they could easily get back to their country. The sea route also allowed the Danish Resistance to get out of the country over 7,000 of Denmark’s 8,000 Jews” (Source).

At this point, they focused mainly on modes of transportation, such as trains and ships. They also targeted industries and factories. The attached some 1,500 trains and another 2,800 industries.

[Below: Jeanne d’Arc School on fire.]