Battle of Philippi

On June 3, 1961, the “first inland battle of the Civil War” began in what is today West Virginia. It was also probably considered one of the shortest battles in history – lasting a mere 20 minutes. With such a short battle and no fatalities, it’s barely receives a footnote in American History textbooks (but, then again, WWI itself is barely a footnote, so take that into context).

Additionally, Philippi was so small that it didn’t even hold any military significance. What it did hold was a very good chance, for Major General George B. McClellan to be prompted to the commander of the Amy of the Potomac, the largest Union army.

Philippi did allow the Union troops to “secure the critical river crossings and rail junctions” (Source). Because, in the neighboring town of Grafton, about 25 miles to the north of Philippi, there was a bit of land that held military significance – railroad crossings. Here, the Parkersburg-Grafton Railroad joined the Baltimore & Ohio. And, this was only the “only continuous east-west connector between the East Coast and the Ohio River and the states of the Old Northwest” (Source).

So, Union troops of about 1,600 strong, under the command of Col. Benjamin Kelley, boarded a train for Thornton, where they would disembark and marched toward Philippi under the cover of darkness. Meanwhile, another group of soldiers, numbering some 1,4000 men, under the command of Col. Ebenezer Dumont, were marching south on the town. They would launch a two-prong assault against the Confederates.

Both groups arrived at the appointed time.

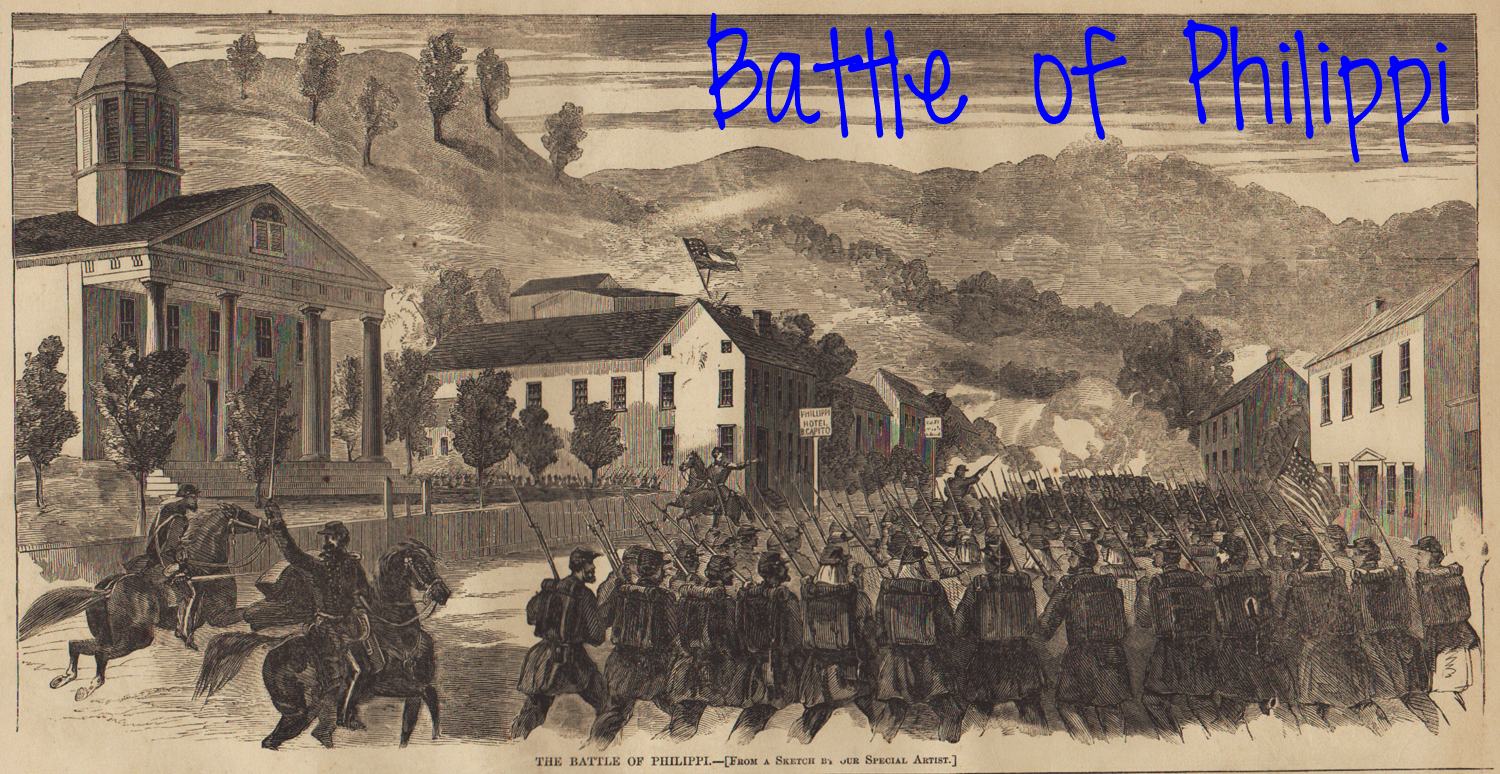

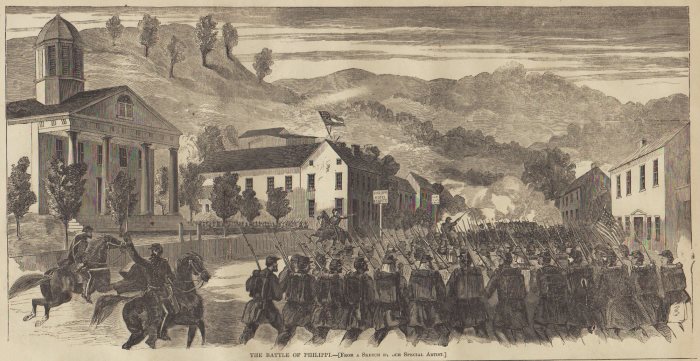

[Below: Colonel Dumont’s troops fire on the enemy]

Meanwhile, General Robert E. Lee sent Mexican War veteran, Col. George Porterfield to Grafton to organize troops. Unfortunately for him, he wasn’t nearly as successful as McClellan. For starters, Lee had greatly underestimated the level of hatred for the Confederates in West Virginia. Porterfield only managed to assemble a handful of troops and whatever weapons they owned themselves. Furthermore, they had next to no military training. Of course, Lee did receive some reinforcements, along with 1,000 rusty muskets and 1,500 percussions caps, all meant for shotguns.

Not surprisingly, Porterfield was unable to hold Grafton.

But, then, Porterfield received word about McClellan’s plans. He properly moved his troops to Philippi, where the Union army quite literally found them sleeping. While some of the Confederates stood their ground, the majority of them fled, “giving the battle the derisive nickname ‘the Philippi Races’” (Source).

Truthfully, the Philippi battle was given a bit of a false start. See, Matilda Humphries, spotting their approach, sent one of her sons to warn the Confederates. He was quickly captured. “In response, she fired her pistol at the Union troops. This shot was misinterpreted as the signal to begin the battle” (Source). The Union began attacking. The Confederates . . . didn’t.

Mercifully, Porterfield managed to keep it together. “He managed to organize a rapid retreat, escaping with all but fifteen men” (Source).

Unfortunately, Colonel Kelley was injured during the very brief battle, suffering from a pistol shot to the chest. He did survive, though, and was promoted to Brigadier General, in command of the Department of West Virginia. Dumont was also promoted. He however, decided to join Congress, instead of furthering his military career. McClellan won accolades for his successful planning. From here, he went on make plans for what would become the Battle of Rich Mountain.

Meanwhile, Porterfield underwent a court-martial inquiry. He was exonerated, but never again held field command again.

[Below: Battle of Philippi]

Up Next:

Battle of Rich Mountain