The Battle of Neuve-Chapelle

The first major battle of 1915, the battle of Neuve-Chapelle was fought from March 10-13 between the British (with the Canadians and Indians) and the Germans. The idea for the attack came from Sir John French, Commander-in-Chief of the BEF. Initially, the attack was meant to only be part of a wider offensive in the Artois. However, the British troops fighting in Ypres were late, making Neuve-Chapelle a major battle, by it’s own right.

At any rate, French’s plan was to capture Aubers, pressing the Germans into Lille. This would, he hoped, reduce the German salient in Neuve-Chapelle (while severing German rail communications) and allow the British the ease some of the pressure the Germans were putting on the Russians. This would make it the first major attack of the Great War that was launched by the British. And according to the French and Russians, it was about time for the British to start pulling their weight.

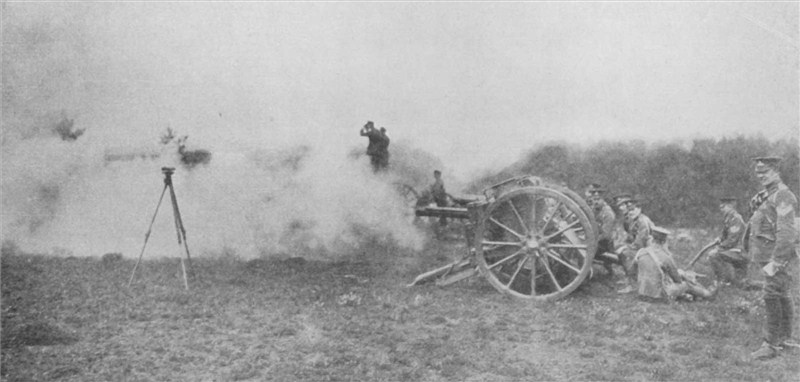

At 8:05 on March 10th, the British First Army under the command of Sir Douglas Haig with “342 guns barraged the trenches for 35 minutes, partially directed by 85 reconnaissance aircraft flying overhead. The total number of shells fired during this barrage exceeded the number fired in the whole of the Boer War” (Source).

Following this, they opened up to attack the German trench lines across a 4,000-yard-long front. This one lasting a mere 30 minutes. The Battle of Neuve-Chapelle was significant for another reason, though. “The British employed aerial photography on a large scale for the first time at Neuve-Chapelle, precisely mapping out the enemy trench system to guide the bombardment and infantry advance” (Source).

Lest one think that the British alone did the firing, during this second half hour, in some areas, entire British units were taken out by German fire. Further back, because not one single Brit managed to come back, commanders actually believed their men had been successful. When in fact, just the opposite was true.

The Germans were putting up quite the fight, particularly that of the 11th Jäger Battalion, but the British were persistent. They continued to barrage the Germans to such an extent that it made it nearly impossible for them to advance successfully.

Nearly, that is because after 5 hours of fighting, the British had actually managed a significant advance. However, with no direct order coming from the rear, they were forced to stall.

And that was their downfall.

Because during their stall, the Germans were busy bringing in reserves. By the time the British were ready to advance, they found more German strong points than they had expected. And this was just the beginning. Because lines had moved, making their previous intelligence useless, the British spent a great deal of time wasting precious shells on empty fields. Worse yet, a thick fog was beginning to roll in. Their progress was, at the least, going to be much slower than the previous day. Information was being poorly communicated, making it even harder for them to advance as a unit.

Because of all this, the 11th was pretty much wasted. But the British planned to attack again the next day. Of course, little did they know that the Germans were planning the same thing. And they beat the British.

As early as 4:30 in the morning, they began with an artillery bombardment, advancing their infantry a half hour later. But their advance was not nearly as successful as the British advance had been two days earlier. The British troops were well dug in and putting up quite the resistance. And then the British responded with their own attack. Though, a fairly uncoordinated one.

In fact, “the 2nd Scots Guard, having taken a German position, had to withdraw after being shelled by their own side” (Source). Nevertheless, the Allied forces made surprising advances.

Although their shelling on the 13th lasted barely two hours, they managed to take some of the land they had lost back in October 1914, “but further progress towards Aubers – which had escaped artillery bombardment, and where the front line wire was thus undamaged – proved impossible; of some 1,000 troops who attacked Aubers, none survived” (Source). Nevertheless, they managed to take some 1,200 German prisoners. The Battle of Neuve-Chappelle was over.

Both Allies and the Germans suffered some 11,2000 casualties on each side.