Battle of Rich Mountain

In June of 1861, Major General George B. McClellan was given command of the Union forces located in western Virginia. After defeating the Confederates at Philippi, McClellan moved his brigades (mostly consisting of troops from Indiana and Ohio) south, wanting to meet up with the Confederate Lt. Col. John Pegram’s troops.

Meanwhile, in charge of the Confederate troops following their hasty retreat from Philippi, was Gen. Robert S. Garnett. He and his troops fortified two key passes: Camp Garnett and Beverly, wanting to cut off McClellan and prevent him from traveling any further East.

At Camp Garnett, itself, the Confederate Lt. Col., John Pegram, was in command with some 1,300 men and 4 cannons. McClellan, meanwhile, had some 5,000 men and 8 cannons. The Confederates thought that they had McClellan beat. But McClellan had a devious plan, himself.

It was simple, really. He’d “feign an attack against Garnett at Laurel Hill while he sent the bulk of his force against Pegram at Rich Mountain” (Source). So, while McClellan waited at the western base of Rich Mountain in northwestern Virginia, he sent Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans on ahead.

On the morning of July 11th, Rosecrans set out with David Hart and roughly 1,917 men. Up the mountain “they struggled, through the dense woods, delayed by missed directions and drenched by rain” (Source). At 11 o’clock that morning, Rosecrans halted his troops long enough to get a message off to McClellan, per their plan.

See, he and McClellan had planned this all out carefully the night before. Rosecrans would set out, heading towards the enemy’s rear. McClellan would wait until he heard the firing, then he’d set out with his own troops for a frontal attack. As planned, once Rosecrans drew close, he sent out Colonel Mahlon Manson to “deploy skirmishers from his 10th Indiana Regiment” (Source). This would be the one and only message that Rosecrans would manage to get to McClellan, despite their plan for hourly updates.

And the further delayed Rosecrans became, the more worried he became that the Confederates were already aware of their movement. Unfortunately, he was right.

The Confederates had already been alerted to Union movement. And for Pegram’s part, he had long since been worried about an attack from the rear. So, he sent out two companies. To make matters even worse, the courier with McClellan’s reply to Rosecrans mistakenly rode into Pegram’s camp and delivered the letter! So, not only was the courier wounded and captured, but now Pegram knew all about Rosecrans‘s plans.

As a result, Pegram sent out a 310-man strong force of “two squads of cavalry from the 14th Virginia and six companies of infantry from the 20th and 25th Virginia” to the Rich Mountain pass under the command of Captain Julius Adolph de Lagnel (Source). At the same time, he sent out the 44th Virginia regiment to the junction of Merritt Road and the Beverly-Buckhannon Turnpike, under the command of Captain John Mayo Pleasants Atkinson.

But Pegram assumed incorrectly the direction Rosecrans and his troops were coming from. At 2:30 that afternoon, Rosecrans and his men headed towards the Hart farm from the South, not the North.

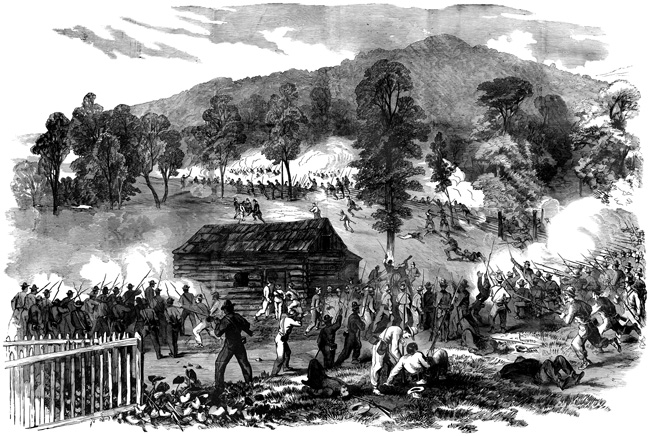

Even then, the Confederates fired at Rosecrans’s skirmishers. Then, they turned around their cannons and fired on the skirmishers. Hidden behind rocks and bushes and trees, the skirmishers returned fire. At intervals, the Confederates would pause long enough to advance, then continue their firing. Unfortunately, though, they couldn’t actually see the Union soldiers, so settled for firing into the clouds of smoke.

The Confederates returned to Camp Garnett, cheering their success. Turned out, though, that they weren’t as lucky as they’d thought. Rosecrans hadn’t been defeated. In fact, he’d suffered very few casualties. Thanks to the woods and the Confederates’s inability to see them, the men had been relatively safe. Confederate brass simply flew over their heads.

Not deterred in the slightest, Rosecrans determined to attack, despite more problems that delayed his advance almost another hour. Nonetheless, they pushed forward to the Hart farm.

Frightened artillery horses pulling the ammunition caisson became unmanageable and stampeded down the road, carrying away their drivers and most of the ammunition. They soon collided with a brass six-pounder being pulled from Camp Garnett, which De Lagnel had requested. Drivers were hurled from their seats, a dozen horses were injured or killed, and their mangled bodies were mixed with smashed equipment as the artillery piece careened down an embankment.

While everything on the Confederate side was a bit chaotic, Rosecrans and his men were spending the night on top of the mountain. The next morning, Rosecrans was informed that the enemy was attempting to flee. Moving on to Camp Garnett, he found the Confederates waving the white flag. Some 170 men, most of whom were sick or injured, surrendered to Rosecrans. Their surrender included their wagons, artillery, equipment, and even the quartermaster’s store.

Meanwhile, McClellan’s force was only a short distance from Fort Garnett. Reaching the camp himself, he found Rosecrans in occupation. Since that had successfully been taken care of, McClellan and his men moved across Rich Mountain.

On July 13, Pegram and about 600 additional men surrendered to McClellan at Beverly. Only about 40 of his men didn’t surrender. Each side suffered roughly 70 casualties.

Up Next:

Battle of Big Bethel