Battle of the Falkland Islands

After their victory at Coronel the month prior, Admiral Graf von Spee received the news that the Glasgow was “hurrying back towards the Falkland Islands” (Source). But after his brilliant success at Coronel, it was assumed that Spee would be the one to capture the Falkland Islands.

Meanwhile, Britain was determined to make up for their mistakes, and sent out the battle cruisers Invincible and Inflexible, under Vice Admiral Frederick Doveton Sturdee’s command, to the South Atlantic squadron. They arrived on December 7th. Spee arrived the next day.

Thus, the Battle of the Falklands commenced.

And this time, the British made sure that their battle cruisers were fitted to give them superiority. Unlike with the ships that took part in the Battle of Coronel, Invincible and Inflexible were “fitted with eight 12-inch guns, whereas Spee’s Scharnhorst and Gneisenau each had 8.2 inch guns” (Source). This time, the British were definitely prepared. On top of this, Sturdee had under his command six more curisers: Canarvon, Cornwall, Kent, Bristol, Glasgow, and Canopus.

Spee had no idea that there were British cruisers. His intention was to “raid the British radio station and coaling depot there” (Source). But, upon his arrival, he discovered the British squadron. At 10 that morning, the British cruisers were fully prepared to leave. “The weather now cleared and visibility over a calm blue sea was complete. As the British ships left harbor, the rising smoke smudges on the horizon showed the positions of the five German warships” (Source). The British cruisers began chasing the Germans.

Early that afternoon, Sturdee’s crew met up with von Spee’s. The British opened fire. Spee, in an attempt to gain some time for the rest of his ships to escape, decided to fight. Using his two biggest cruisers – the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau – Spee attacked the British squadron. Invincible was hit.

Thankfully, the damage was minimal.

Spee turned away, hoping to escape. At this point, three of his cruisers – Dresden, Nürnberg, & Leipzig – were being pursued by Kent, Cornwall, & Glasgow. But Sturdee pressed the attack on Scharnhorst and Gneisenau” (Source). Spee fought back.

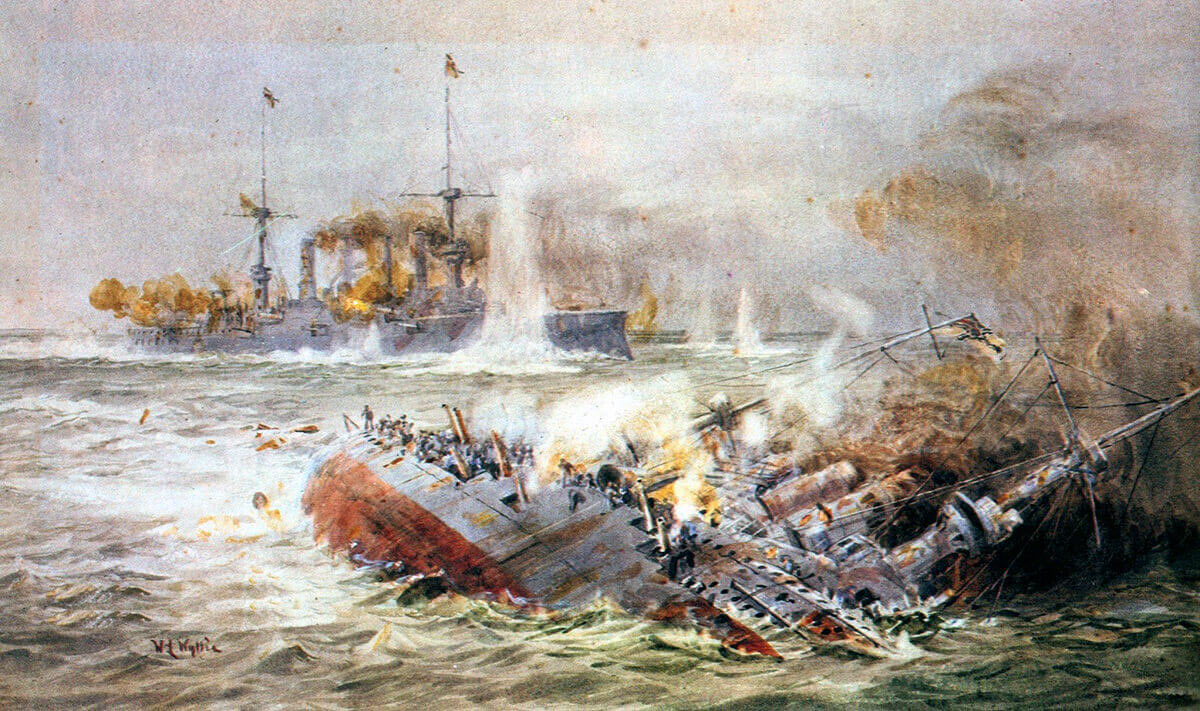

“For over three hours, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau exchanged shots with the two British battle cruisers” (Source). Little damage was being done to the British cruisers, while the German cruisers were enduring heavy damage. By 3:30, Gneisenau was listing terribly to the side and Scharnhorst was in flames – the flames between the decks taking over. Half an hour later, Scharnhorst suddenly ceased firing. At 4:17, Scharnhorst sunk. The entire crew was lost.

With one ship down, Invincible joined Inflexible in the attack against Gneisenau. With the two British ships attacking, Gneisenau was forced to slow to such a speed that Carnarvon was able to catch up and join the fight – prior to this, Admiral Stoddart aboard the Carnarvon had been engaged with ships outside the harbor. Also, due to Carnarvon’s and Cornwall’s slower speeds, they had a hard time keeping up with the race. But now Carnarvon was joining the battle. And just in time, too, because Inflexible was having a difficult time shooting at Gneisenau with all of the flagship’s smoke.

Also at about this time, the weather began deteriorating. Rain began to fall, reducing the visibility even more. “At 5:50pm, Gneisenau turned towards Invincible and stopped. The two battle cruisers closed in. The German ship was listing heavily to starboard. Her firing was sporadic and then ceased” (Source).

Convinced that Gneisenau could no longer carry on, Sturdee called for a cease fire, only to have Gneisenau suddenly pick up the fight once more. At 5:45, Gneisenau stopped firing again. This time it was clear that she was sinking. With the two largest of Spee’s ships out of commission, it was time to turn to the three smaller ones.

[Below: SMS Scharnhorst sinking in the foreground and SMS Gneisenau burning]

The remaining German ships were faster than the three British cruisers sent after them, and war in a way outgunned them. But many of them were also low on ammunition, thanks to the Battle of Coronel.

Captain Luce aboard Glasgow decided to start the attack with Leipzig. Cornwall joined in the fight with Leipzig while Kent and Nürnberg were left to battle it out.

By 4:45, Glasgow and Cornwall had managed to kill Leipzig’s gunnery lieutenant, severely handicapping the German light cruiser. By 6, the rain had picked up and Captain Luce knew they had to wrap the battle up, so he signaled to Cornwall to open fire with lyddite. Leipzig was set ablaze. Even then, Leipzig continued to fire back for another hour. At 7, her guns fell silent. It wasn’t until well after 7:30 that the crew members gave the ceasefire signal. At 9:23 Leipzig sank. Five officers and 13 seamen were rescued by the British.

During the battle with Leipzig, Cornwall was hit eighteen times and was listing to port. Glasgow was hit twice, losing one man while four were wounded. Cornwall lost none.

Meanwhile, Kent was busy chasing Nürnberg. Unfortunately for Kent there had been no time to take on coal at Port Stanley, meaning she was very short on fuel. Thus, “Captain Allen, the captain of Kent, ordered that every item of wood be taken to the engine room for the stokers to load into the burners. Woodwork was stripped from all the fittings and even the officers’ trunks were burnt” (Source). By 6 pm, Kent had closed in on Nürnberg enough to open fire and cause damage.

A mere 10 minutes later, Nürnberg had lost speed, was on fire, and had only two operational guns. All this together was devastating. Two more bullets destroyed her forward turret. By 6:25, she was stationary and silent. The bridge was on fire. No crew could be seen. Five minutes later, Nürnberg hauled down her ensign. At 7:30, Nürnberg sank. Only seven members were rescued.

However, during the attack, Kent had undergone serious damage. She had been hit forty times during the battle. The radio room was wrecked. Four men were killed and twelve were wounded. Of the German ships, only Dresden escaped. Germany had lost four ships and some 2,000 sailors. Meanwhile, the British suffered only 10 deaths.

“The battle of the Falklands and the destruction of the Dresden ended the German presence on the high seas” (Source). From here on out, the bulk of the German naval threat came from U-boats.

[Below: HMS Kent – damage done to the officers’ heads]