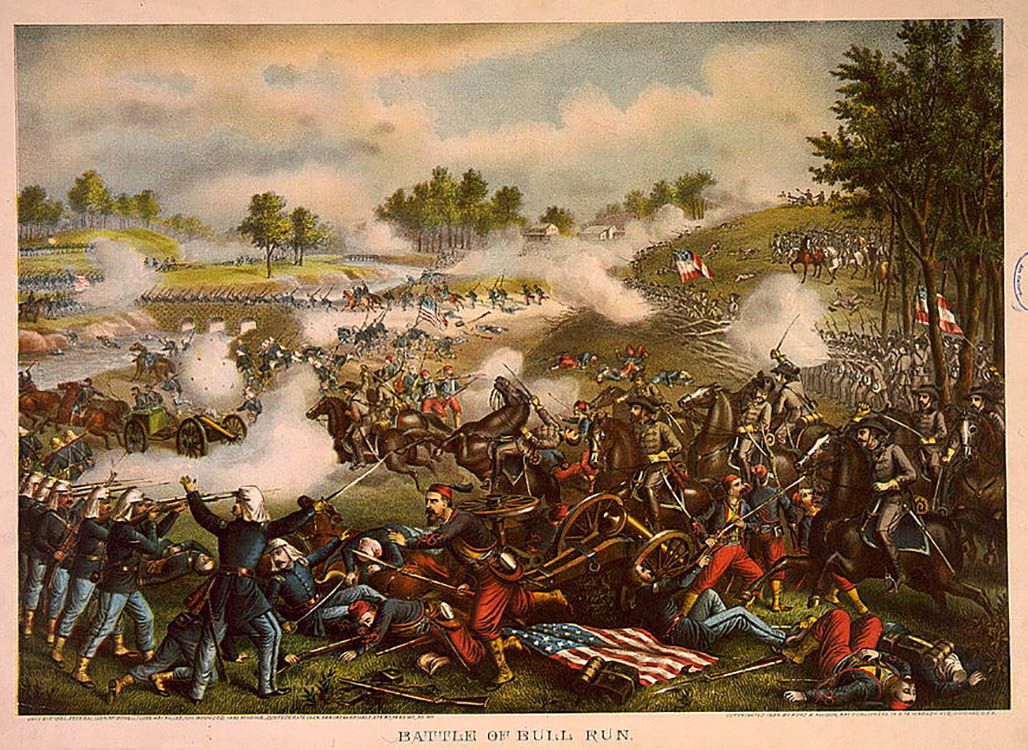

1st Battle of Bull Run

On July 21, 1861 one of the biggest and best known battle of the Civil War began, the 1st Battle of Bull Run. Near Manassas Junction in Virginia, the Union and Confederate armies clashed once again.

Just five days prior to that, the brand new Union commander, General Irvin McDowell, marched through the streets of Washington D.C. With him were 35,000 soldiers, all raw recruits. Most of them had no idea what they were facing. Maybe that was why it was so easy for them to swagger down those D.C. streets, confident in their victory. They looked so impressive, that, “as excitement spread, many citizens and [congressmen] with wine and picnic baskets followed the army into the field to watch what all expected would be a colorful show” (Source). It’s not often that war is seen as entertainment. The recruits, for their own part, were busy picking blackberries and filling their canteens in the river.

Their ultimate goal was reaching the railroad junction at Manassas, where the Orange Alexandria Railroad and the Manassas Gap Railroad met just west of the Shenandoah Valley. If they could take this land, they would have a clear approach to capturing the Confederate capital. And what a victory that would be!

Two days later, the Union army finally reached Centreville. They were no a mere five miles from Bull Run River. But ahead, guarding the “fords from Union Mills to the stone Bridge” were 22,000 Southern troops under the command of Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard. (Source).

The next few days were spent in scouting, at least on McDowell’s side. But, then, on the morning of July 21st, McDowell and his troops attacked.

First off, he sent two divisions towards Sudley Springs Ford, back around the Confederate left. The other division he sent out towards the Warrenton Turnpike, where it crossed Bull Run at the Stone Bridge. The main job of this second division was to distract the Confederates to allow the 1st group to continue.

At 5:30 that morning, a rifle shattered the morning air.

The battle had begun.

But there was one major problem on the Union side. Thanks to intelligence (pre-pre-OSS days, apparently), the Confederates were already aware of the Union’s plans. Already knowing that the division sent to Stone Bridge was merely a diversion, Colonel Nathan Evans sent his men towards Matthews Hill.

Back at Henry Hill, the Confederates were busy setting up reinforcements. Brigadier General Thomas Jackson (the famous Stonewall) had his Virginia brigade, under Col. Wade Hampton as well as Col. J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry set up across the crest of the hill, along with artillery.

Meanwhile, McDowell’s men were marching towards Henry Hill. Here, “contesting batteries engaged in a fierce fight” (Source). It was during this very fight that Jackson received his famous nickname.

Shelling had begun across Bull Run River. Union troops crossed the Sudley River. They managed to push 4,500 Confederates back up Henry Hill by midday. All of the congressmen, reporters, and other spectators cheered on the winning Union soldiers.

But they were a bit premature, because more and more Confederate reinforcements continued to arrive. By 4 that afternoon, Beauregard ordered the Confederates to counterattack. This is what became wildly known as the “Rebel Yell,” as Confederates, screaming, broke through Union lines. But Confederates didn’t just take down Union soldiers, but also the spectators. “As McDowell’s Federals retreated chaotically across Bull Run, they ran headlong into hundreds of Washington officials who had been watching the battle while picnicking on the fields east of the river, now making their own hasty retreat” (Source). Well, at the very least, they caused the spectators to retreat in haste.

Meanwhile, Jackson received word from Brig. Gen. Barnard Bee that McDowell’s men were about to break Confederate ranks. Jackson told Bee to make sure his men stood strong. To his men, Bee used Jackson as a reference, “Look at Jackson standing like a stonewall.” It seemed to work, because the Confederates charged the Union line, overtaking it, and capturing all of their guns. This, unfortunately for the Union, changed the course of the battle.

Around noon, the Union stopped their retreat to regroup. Thus, a lull in the fighting lasted for about an hour, long enough for both sides to reform their lines. When fighting resumed, each side was desperate to force the other side off Henry Hill.

This lasted for another four hours, when the Confederates received even more reinforcements, arriving to the rear of the Union forces. With their advance, McDowell and his men were forced to finally withdraw. Their withdraw was at first orderly, but only orderly until they met up with the still retreating Washington spectators. At this point, retreat became chaotic and soldiers began to panic. Had Confederates not also been in chaos, themselves, they may have followed the Union. However, they failed to do so.

After his defeat in battle, McDowell was replaced by Major General George B. McClellan. On the Confederate side, the two armies of Gen Joseph E. Johnston and Gen. Beauregard were combined and Gen. Robert E. Lee was put in command.

Overall, the Confederates suffering 1,750 casualties while the Union suffered 3,000. Because of these large numbers, both sides – the North in particular – were forced to realize that this would not be a short war with an easy win. This was going to be a long, bloody war.

/First_Battle_of_Bull_Run_Kurz__Allison-5b3a498246e0fb00379a1e74.jpg)

Up Next:

Battle at Wilson’s Creek