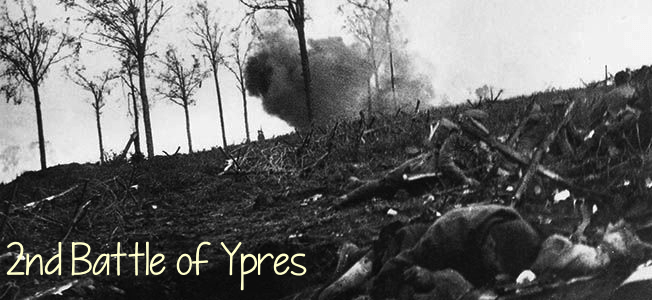

2nd Battle of Ypres

2nd Battle of Ypres On April 22, 1915, the German 4th Army mounted a surprise attack against the Allies on the Western Front in Ypres,… Read More »2nd Battle of Ypres

2nd Battle of Ypres On April 22, 1915, the German 4th Army mounted a surprise attack against the Allies on the Western Front in Ypres,… Read More »2nd Battle of Ypres

The Battle of Neuve-Chapelle The first major battle of 1915, the battle of Neuve-Chapelle was fought from March 10-13 between the British (with the Canadians… Read More »The Battle of Neuve-Chapelle

The Battle of Mons (1914) On August 23, 1914, Europe saw its first battle of WWI. This was the “first confrontation on European soil since… Read More »The Battle of Mons (1914)