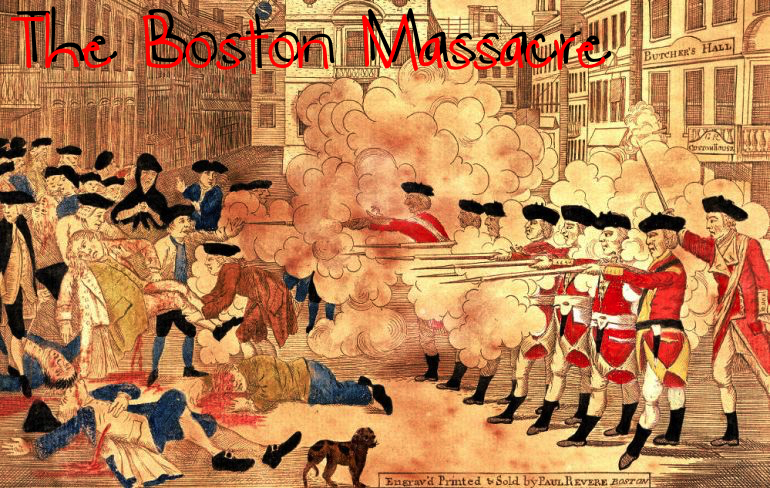

The Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre What began as a street brawl on King Street in Boston on March 5, 1770, turned into what today we know as… Read More »The Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre What began as a street brawl on King Street in Boston on March 5, 1770, turned into what today we know as… Read More »The Boston Massacre

Too Many Acts: Four Acts That Led to the American Revolution How many people want their entire paycheck to go to the government in the… Read More »Too Many Acts: Four Acts That Led to the American Revolution